Treasures from The Archives

“Even in this wilderness I encountered astute people”

That was how Carl Fredrik Fredenheim described meeting an Italian bishop in the wetlands near the Bay of Naples in spring 1788.

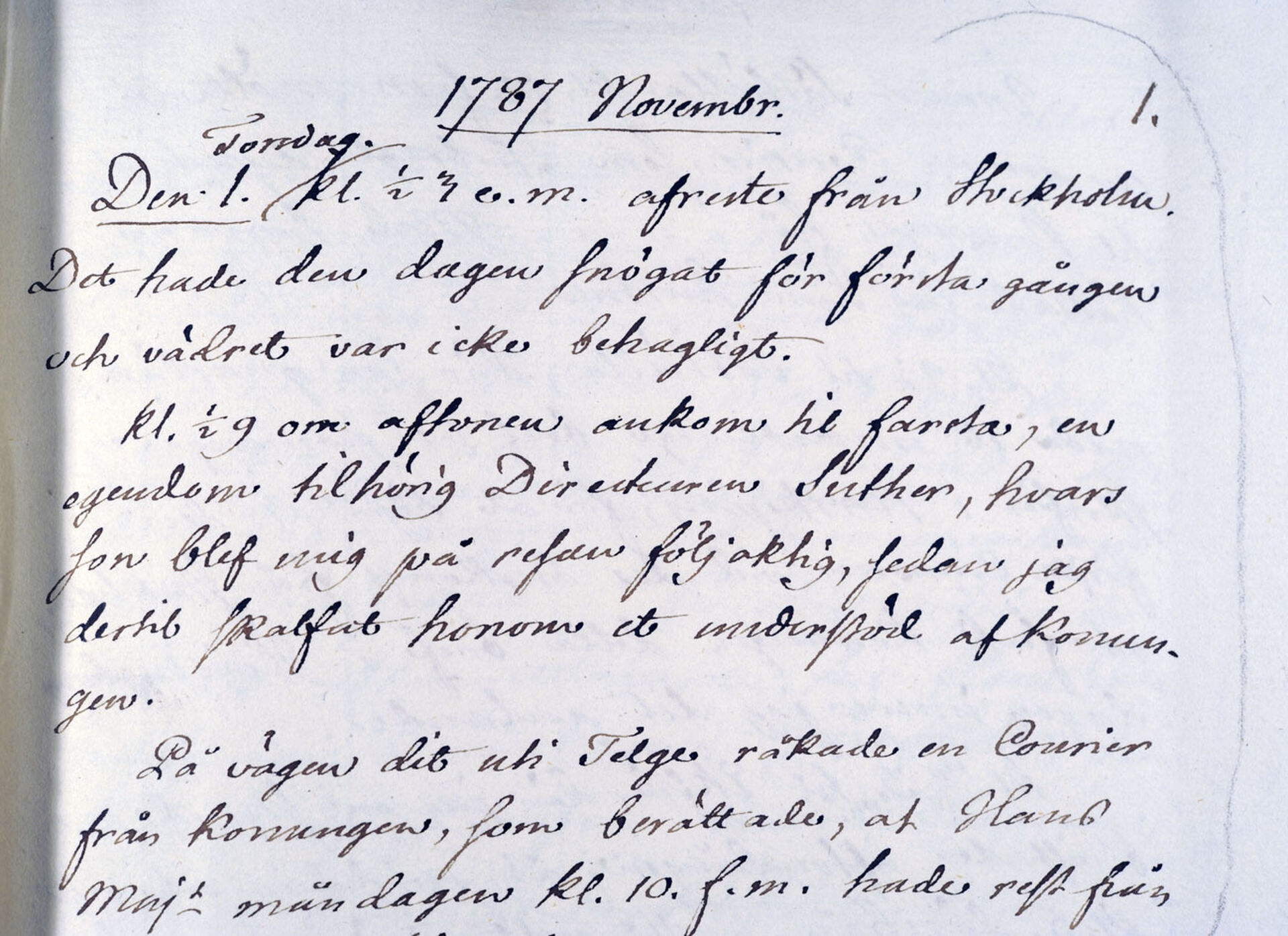

Fredenheim, a young secretary at the foreign ministry in Stockholm, was set to take over as superintendent of the royal art collections. On a chilly Thursday afternoon in November 1787, just after the first snowfall in Stockholm, he embarked on his long journey south through Europe. The purpose of this grand tour was to gather information on Gustav III’s collection of antique marble sculptures, which the king himself had purchased on a visit to Rome some years previously. Now he had entrusted his secretary with the task of expanding the collection.

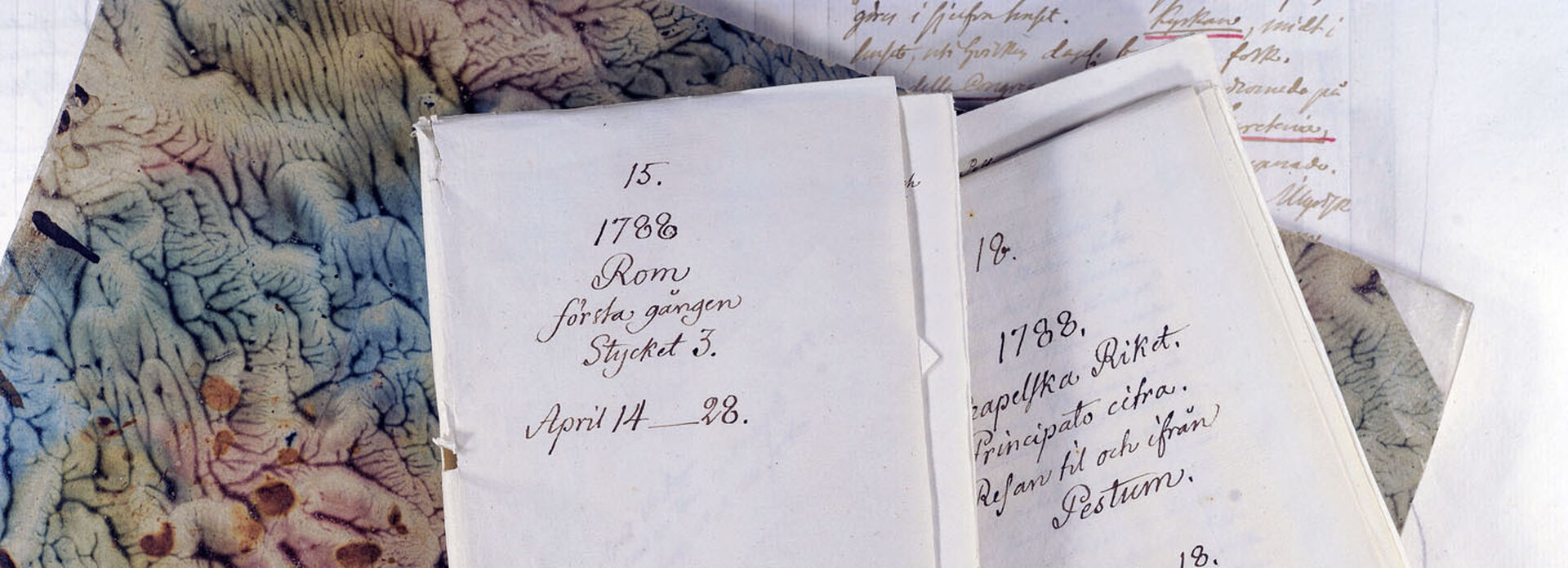

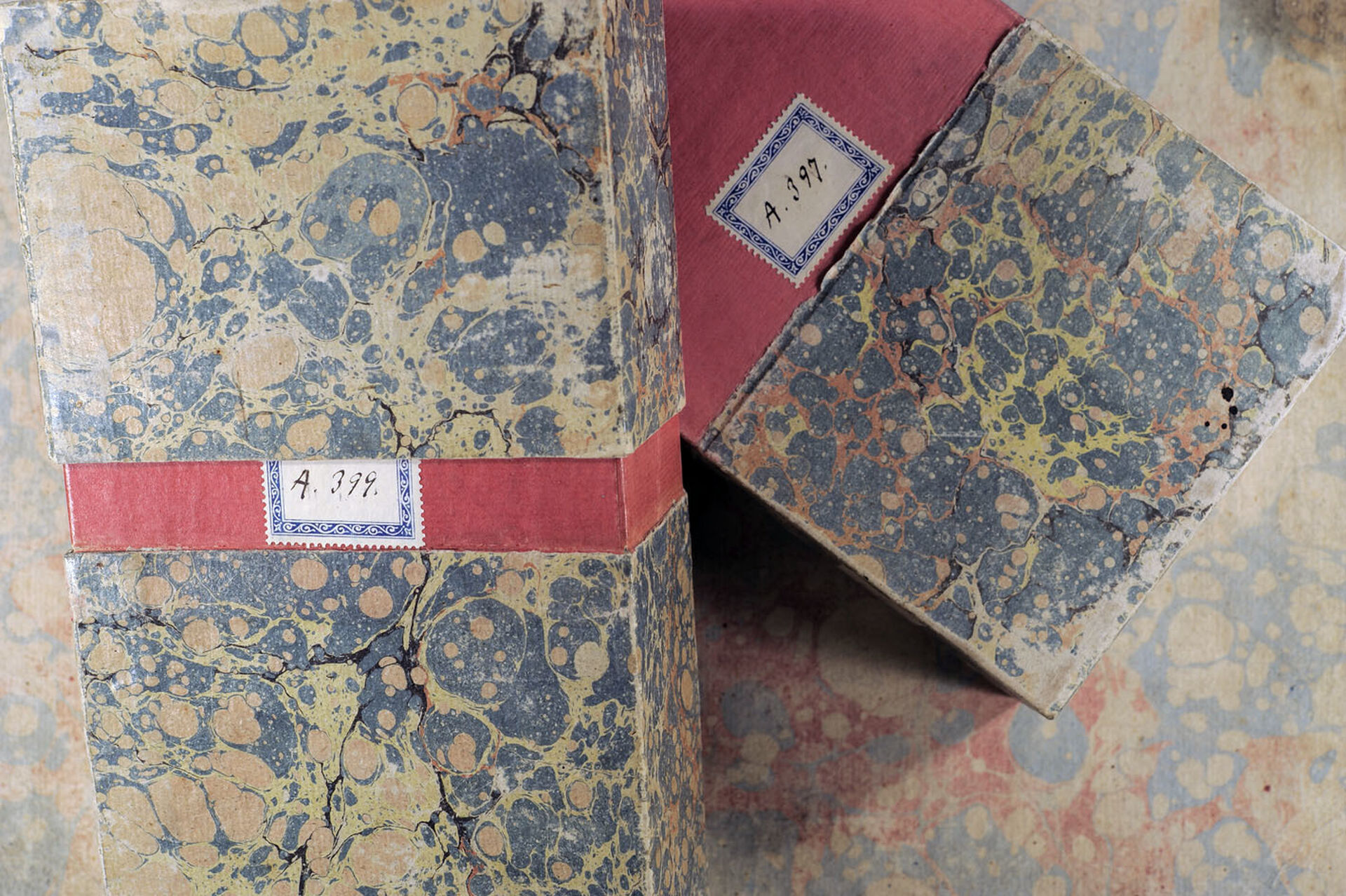

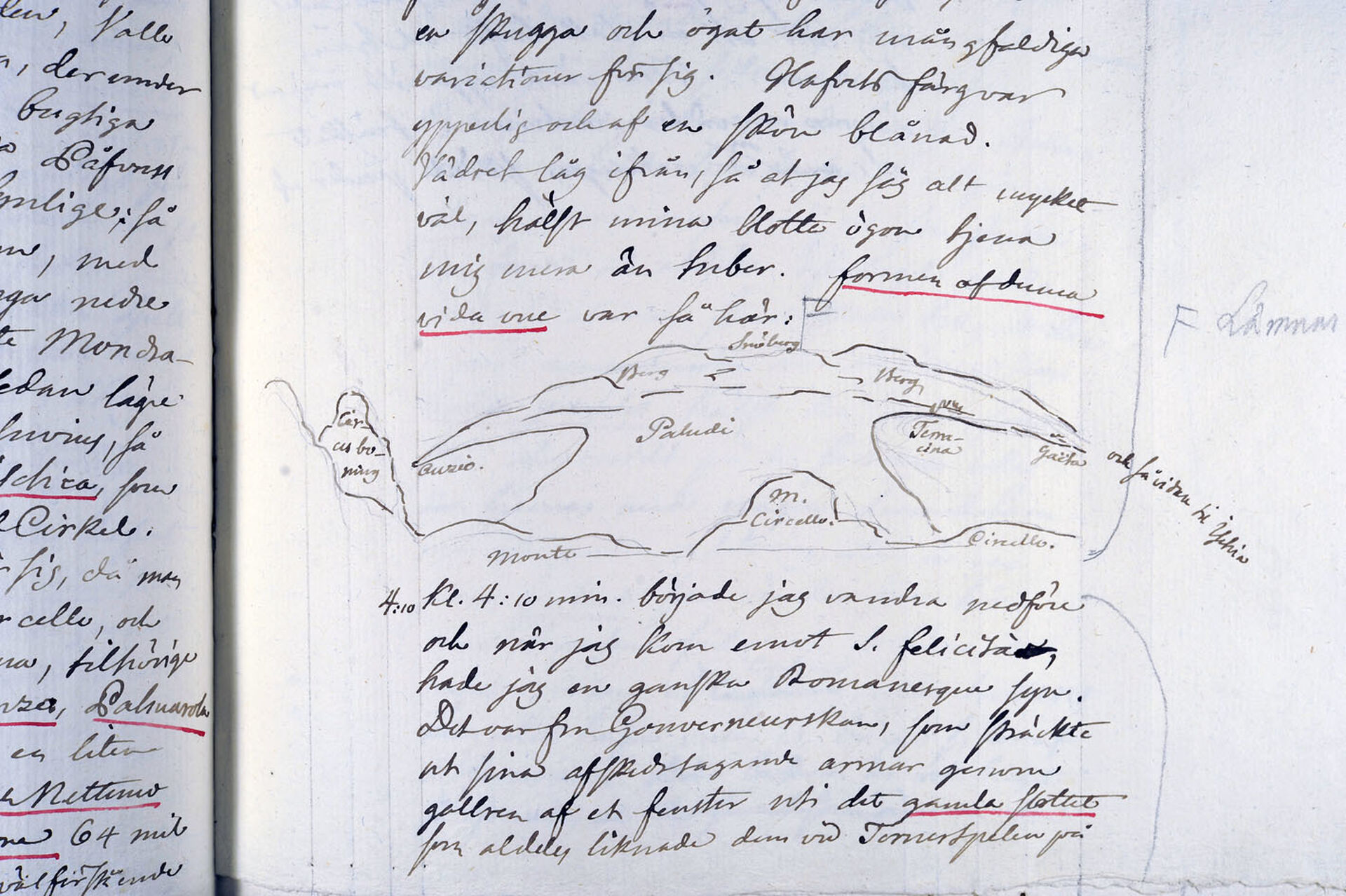

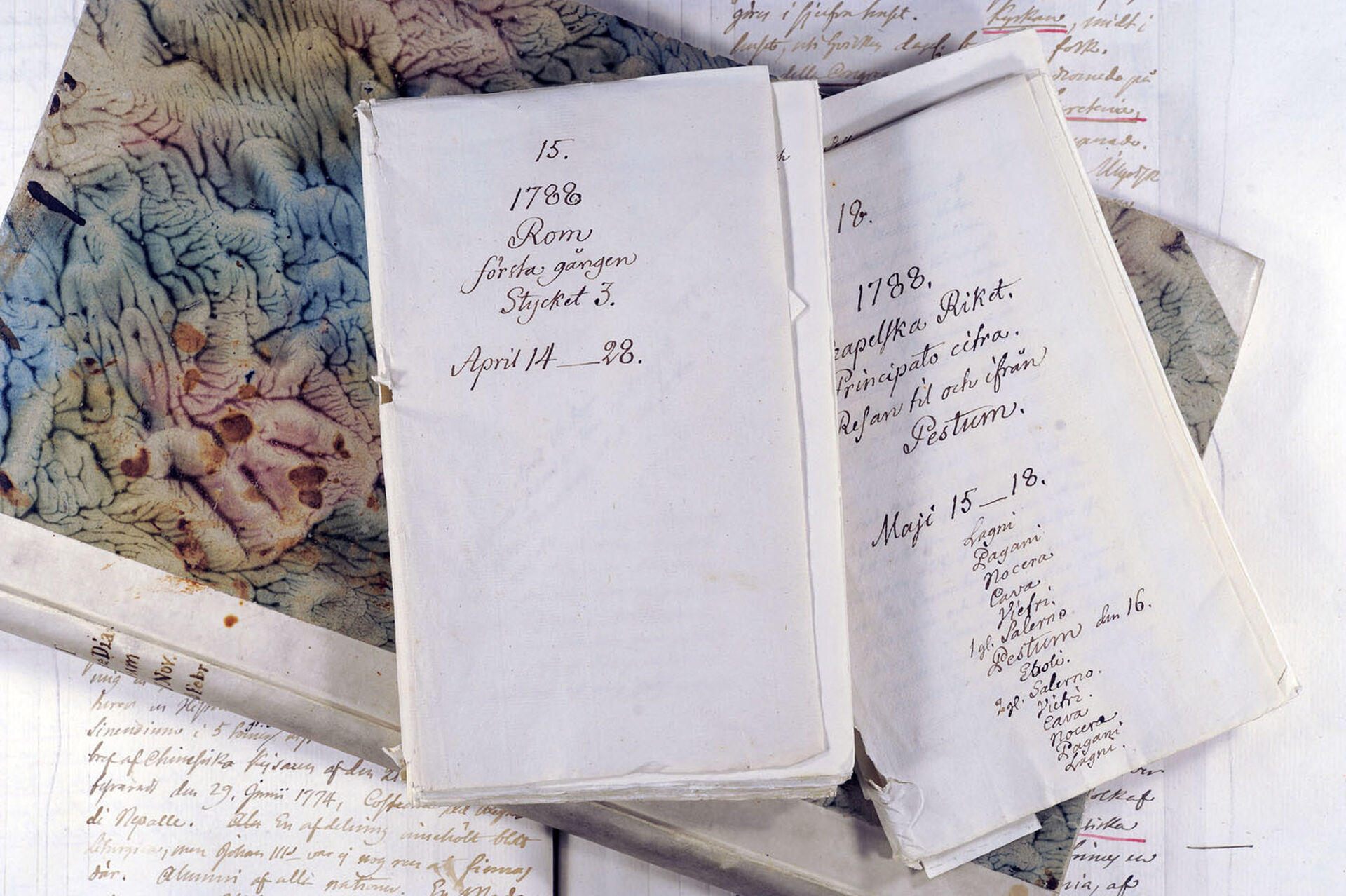

Fredenheim’s travel journal is a bound volume with beautiful marbled covers and a parchment binding. The first page contains a quotation from a traveller’s letter sent from Turin in the spring of 1758. The writer was Mme de Boccage, the French poet, dramatist and author, and the quote comes from her epistolary novel about a trip to Italy. Travel writing in journal or letter form was a popular literary genre in the 18th century. Such books were translated into various languages and read by Europe’s educated bourgeoisie. We can assume that Fredenheim was inspired by the illustrious Mme de Boccage and, had the French revolution not intervened, had planned to meet her in Paris on his way home from Italy in 1789. Fredenheim was a diligent secretary who rounded off every day by recording the day’s events in writing: whom he had met (everyone from the pope to the servants), what they had talked about, what they had eaten, and sometimes what indignities he had suffered (if he was feeling unwell or there were bandits near by).

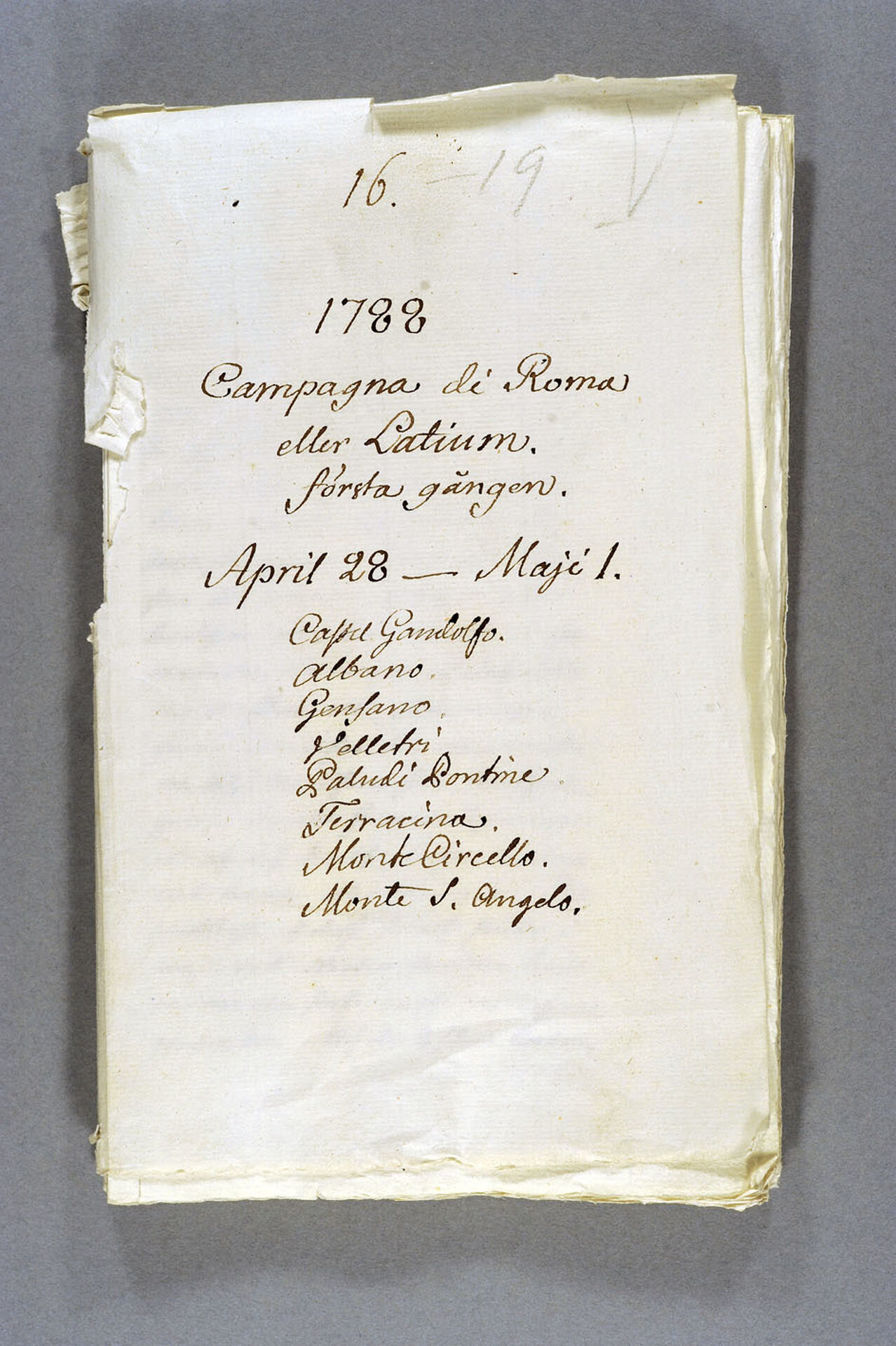

The neatly written journals are kept in chronological order in small, marbled paper boxes in the museum archives. They are fascinating in their detail and, although they have been criticised for presenting subjective opinions on the artworks viewed or the artists visited, they provide a somewhat subjective picture of people, nature and Italian society.

Fredenheim socialised intensively with the nobility of the day, as well as exploring his surroundings on his own. He studied ancient ruins but also trade routes, agriculture and mining operations. At the ancient city of Paestum, amid the wetlands at the mouth of the river Sele, he notes with satisfaction that, even in this wilderness, “astute” people were to be found, since he had spent the day in the company of the bishop of Capaccio and a group of priests who were visiting the area.

Like a true son of the Enlightenment, Fredenheim had a great interest in science. In autumn 1788 he obtained papal permission to carry out excavations at the Forum Romanum. The work involved a team of over 30 men under the supervision of Fredenheim and his associate in Rome, the engraver and art dealer Francesco Piranesi. Piranesi created images of the finds, and the locations were marked on a grid. The excavations are thought to have been among the first of their kind to take a scientific approach. Unfortunately the entire scheme was funded by selling the marble artefacts found, but Fredenheim made sure the most important finds were given to Pope Pius VI, who sent them to the Vatican Museum.

Further Reading

If you want to read more about 18th-century tourism, the English translation of Mme de Boccage’s letters to her sister, Letters Concerning England, Holland and Italy, published in London in 1770, is available in full on Google Books.

Read about Gustav III’s Italian journey in 1783–84 (in Swedish) in Svenska memoarer och bref V, available in full at Litteraturbanken.se.

Maria Nyman: Resandets gränser is a thesis published in 2013 on the subject of Swedish travellers’ accounts of their travels in 18th-century Russia. Available in full online (in Swedish) at DiVA.

Adelaide Hauswolff: En svensk flickas dagbok under krigsfångenskap i Ryssland 1808–1809, Karlstad 1912, available in full (in Swedish) at Projekt Runeberg, is the diary of a Swedish girl held as a prisoner of war in Russia.

John Bell: Travels from St Petersburg in Russia to Diverse Parts of Asia, Glasgow 1763, available on Google Books.

For more about Fredenheim’s travels, including excerpts from his journals and letters (in Swedish), we highly recommend Lars-Johan Stjernstedt: Vår man i Rom, Atlantis förlag 2004.

For more about Gustav III’s contacts with Italy and his collection of classical art, see Anne-Marie Lenander Touati: Ancient Sculptures in the Royal Museum, Vol 1, Stockholm 1998.

//Gertrud Nord, Archivist, Nationalmuseum Archives

More treasuers from the Archives and Art Library