How did architects copy their own and other architects' designs before duplicating machines existed? A collection of tracings at Nationalmuseum shows us 18th-century copying practices by architects Carl Hårleman and Carl Johan Cronstedt.

May 15, 2023

Anna Bortolozzi, guest curator

For architects in the early modern period, copying was both the foundation of their professional training and the endless reality of their daily practice. Copies served many purposes. They provided models and ideas for new projects and they helped architects visualise changes and corrections in the design process. Assistants were often employed as draughtsmen to make fair copies for clients and copies of finished projects to be kept by the architect as a record.

Georg Engelhard Schröder (1684–1750), Giöran Josuæ Adelcrantz. Oil on canvas, 81.5 × 65.5 cm. Finnish National Gallery, S 44, detail. Photo: Finnish National Gallery/Petri Virtanen

Architects’ copying methods

To speed up the copying process and ensure it was accurate, architects had a variety of methods to choose from. The most widespread was a technique for transferring an image by pricking holes. The original was laid on top of another sheet of paper and the principal points were transferred to the copy by pricking through the original with a fine needle. The draughtsman had then to outline the copy by connecting the pricked holes with chalk, pen and ink, straight edge, and compass. This pricking technique was especially well suited for copying straight-line drawings – building plans, elevations and sections – but less helpful when copying organic forms such as decorative elements and furniture, which in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were a substantial part of an architect’s work.

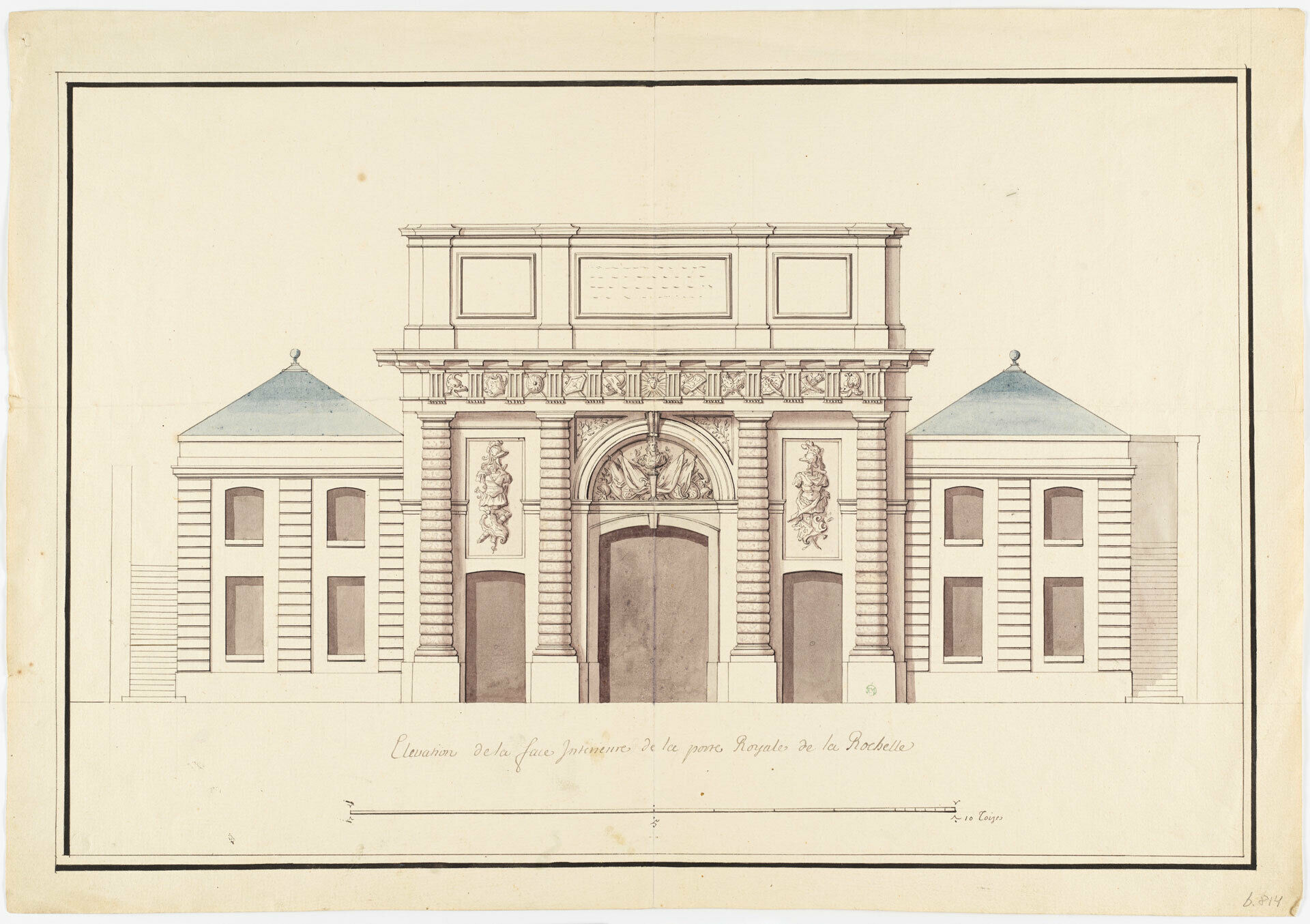

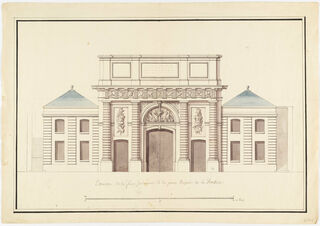

Jean-Baptiste Bullet de Chamblain (1665–1726) after Pierre Bullet, La Porte Royale de La Rochelle, elevation towards the city, c.1689–1692. Pen and black ink over graphite, brush and grey wash, light blue watercolour on white laid paper, 40.5 × 58.1 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH THC 6814.

Detail taken with transmitted light showing pricking to transfer the design

Another method for transferring drawings was to incise the original with a stylus, having rubbed the back of the sheet (or an intermediate sheet) with chalk. This traditional ‘carbon paper’ method, known in Italian as calco, was widely practised by artists and engravers, but there is little evidence of its use by architects in surviving collections of drawings.

Pierre Bullet (1639–1716), Study for a ‘Colonne Ludovise’, a monument to Louis XIV in the form of a victory column, c.1680–1690. Graphite, pen and brown ink, brush and brown wash on three joined sheets of white laid paper, 123.9 × 30 cm. The back is rubbed with black chalk following the outline of the column. Nationalmuseum NMH THC 6858 recto (left), verso (right).

Detail of the recto taken with raking light showing the indented lines made by the stylus used to transfer the design onto another sheet.

An alternative method for copying drawings known since the Renaissance used paper made transparent with vegetable oils or resins (tracing paper, known in Italian as carta da lucido). The original was laid under the transparent paper and traced with precision and ease, without damage to the sheet. Having traced the desired image onto the transparent sheet, the copyist was free to transfer it onto a new working surface by pricking the outlines or tracing them with a stylus.

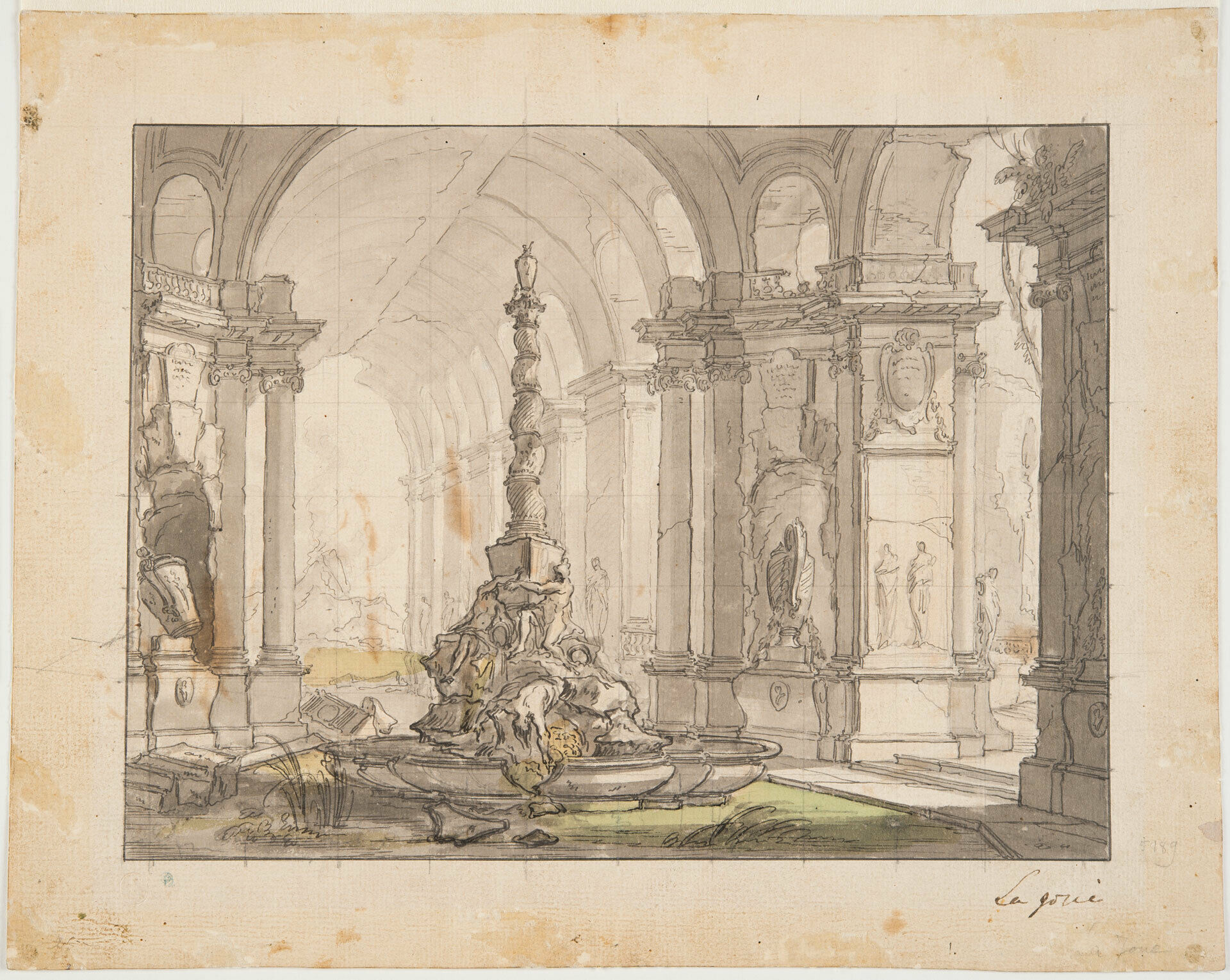

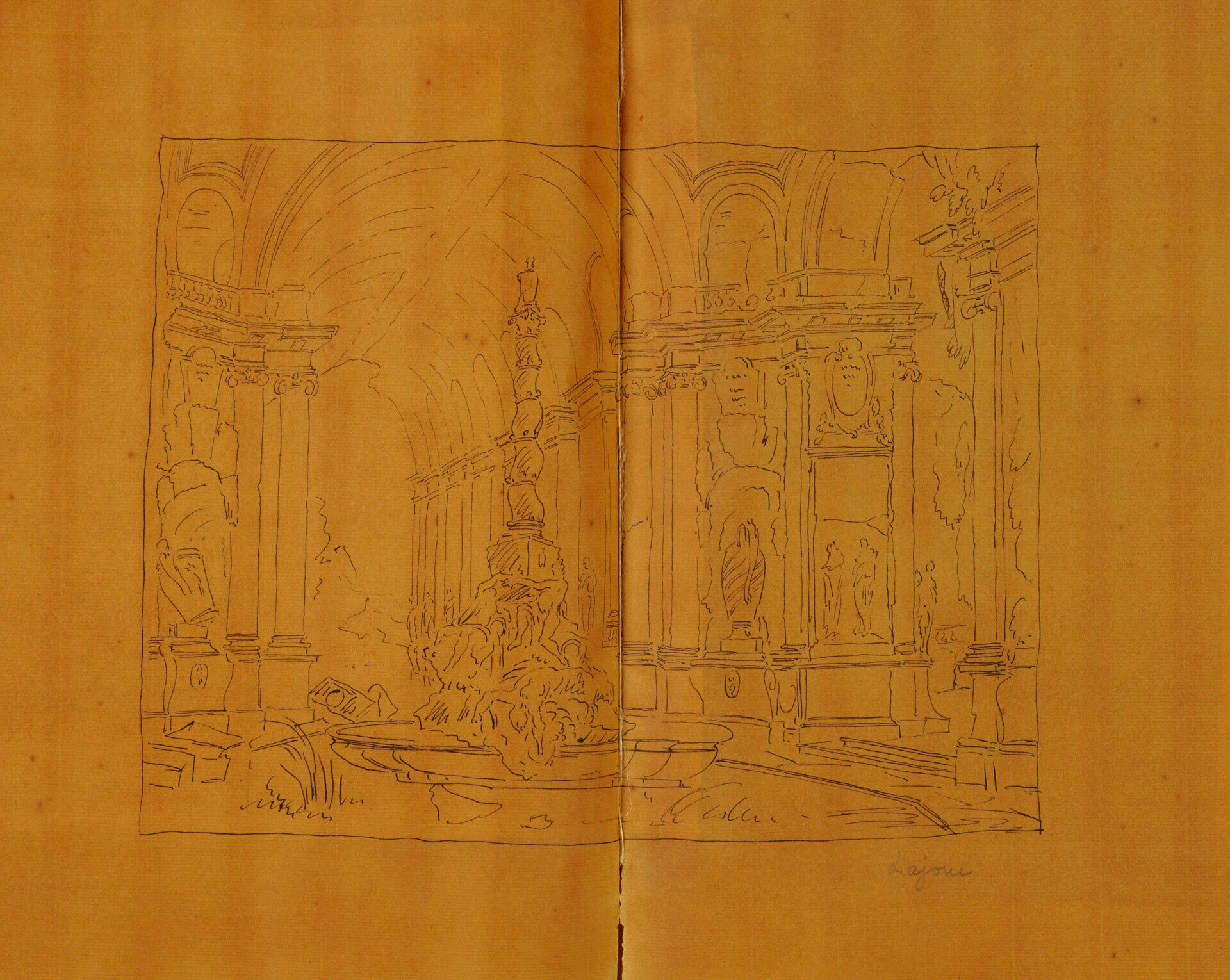

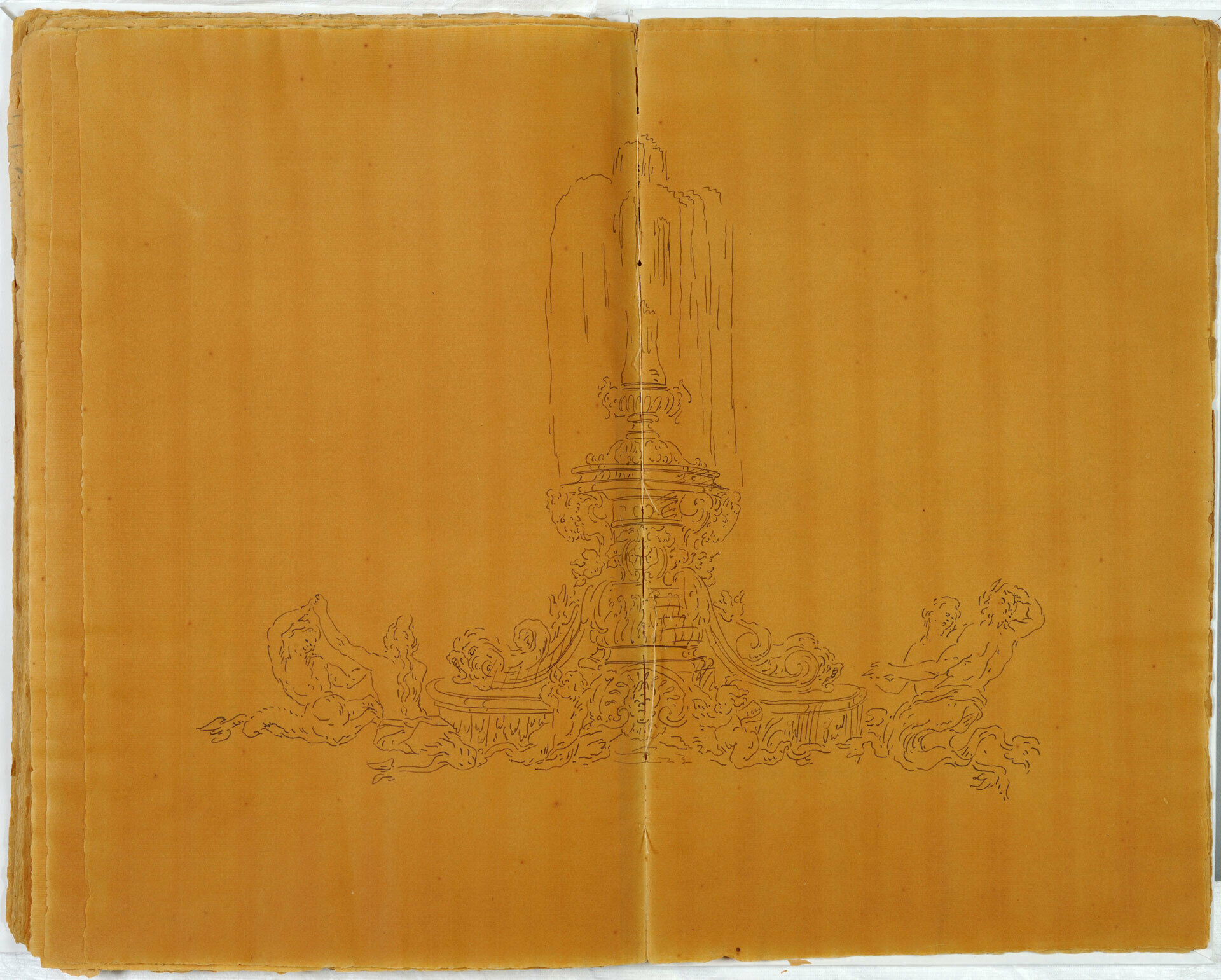

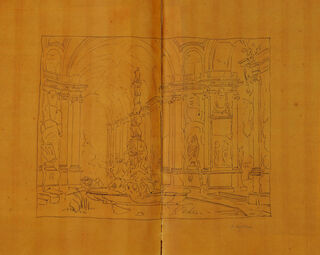

Jacques de Lajoue (1687–1761), Fountain with twisted central pillar set in a colonnade, c. 1730. Graphite, pen and grey ink, brush and grey wash, green watercolour on white laid paper, 23 × 30 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH THC 5189.

Carl Johan Cronstedt (1709–1777) after Jacques de Lajoue, Fountain with twisted central pillar set in a colonnade. Pen and black ink on tracing paper, 39.2 × 48.3 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH A CC 356:30.

Artists’ recipes for making paper transparent are known from the Middle Ages. Cennino Cennini (The Book of the Art, c.1400) said to coat paper with linseed oil. Raffaello Borghini (Il Riposo, 1584) instead recommended walnut oil. Seventeenth-century art manuals suggested the use of warm turpentine oil (known as Venetian turpentine), a natural balsam made by distilling the resin of larch trees. In the French Encyclopédie (1765), turpentine oil and plant oils (either walnut, poppyseed, or hazelnut) are equally recommended.

In time, the oils used to coat paper will darken, giving tracings the characteristic yellow or brownish colour we see today. Turpentine oil has a propensity to dry paper fibres, and that is why tracings are often brittle and damaged. It is likely because of their fragility, but also due to the copies’ chiefly functional role, that architectural tracings dating before 1800 rarely survive.

Architectural tracings in the Nationalmuseum

An exception is a group of over 600 tracings executed in the studios of the Swedish architects Carl Hårleman (1700–1753) and Carl Johan Cronstedt (1709–1777). They are part of a vast collection of architectural drawings in the Nationalmuseum of Stockholm, mainly originating from the professional work of Nicodemus Tessin the Elder (1615–1681), Nicodemus Tessin the Younger (1654–1728), and their successors as head of the Office of the Swedish Superintendence of Public Works.

Martin van Meytens (1695– 1770), Carl Hårleman (1700–1753), baron, superintendent, architect, c.1730. Oil on canvas, 82 × 66 cm. Nationalmuseum NMGrh 1057.

Charles Guillaume Cousin (1707–1783), Carl Johan Cronstedt (1709–1777), count, superintendent, architect, 1743. Plaster, height 70 cm. Nationalmuseum, NMTiS 156.

A significant proportion of the c.15,000 sheets in the collection are copies of French and Italian architects’ designs or projects by Swedish masters. Detailed examination shows that most copies were done using the pricking technique, but that in about the 1720s Swedish architects started making copies using transparent paper.

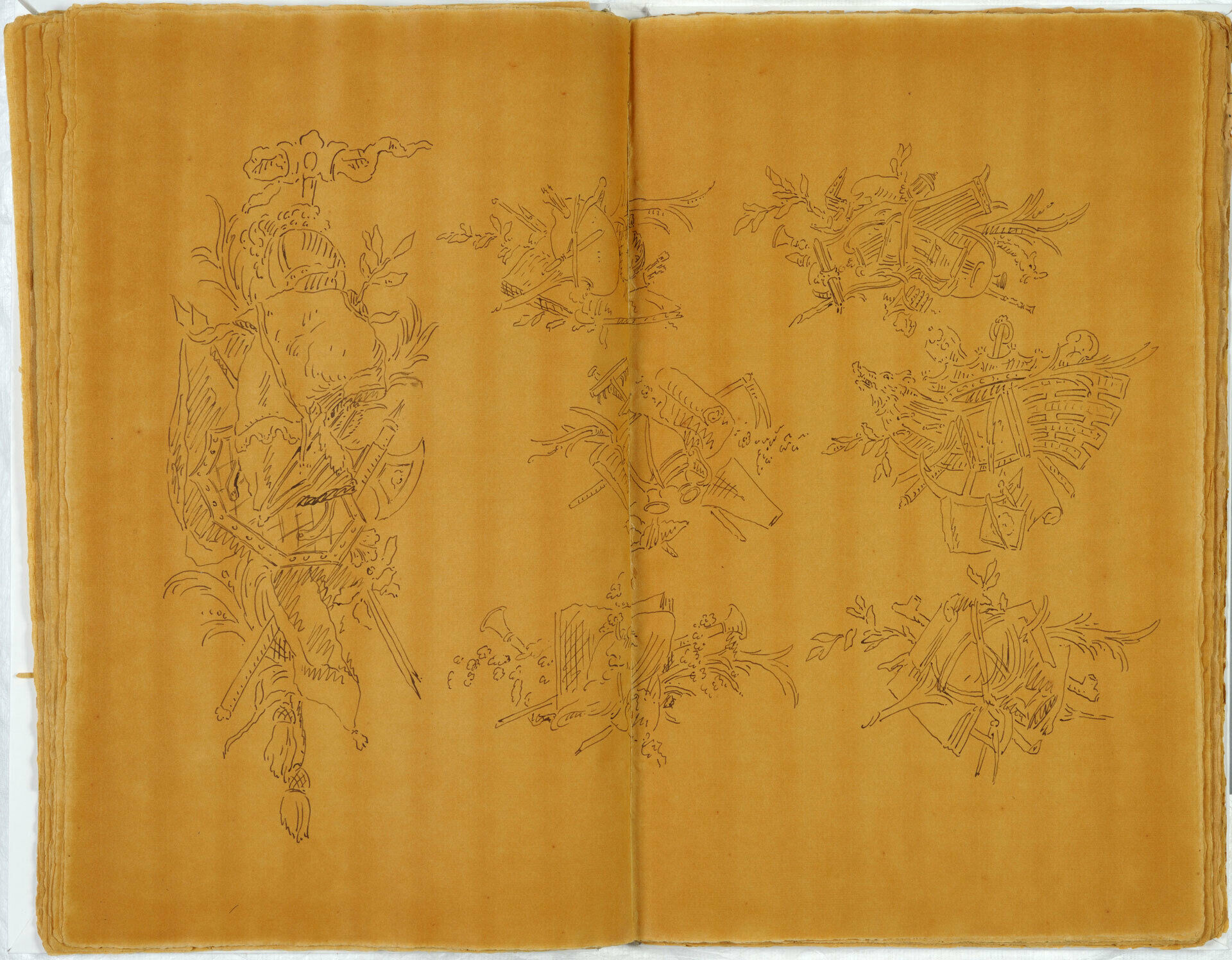

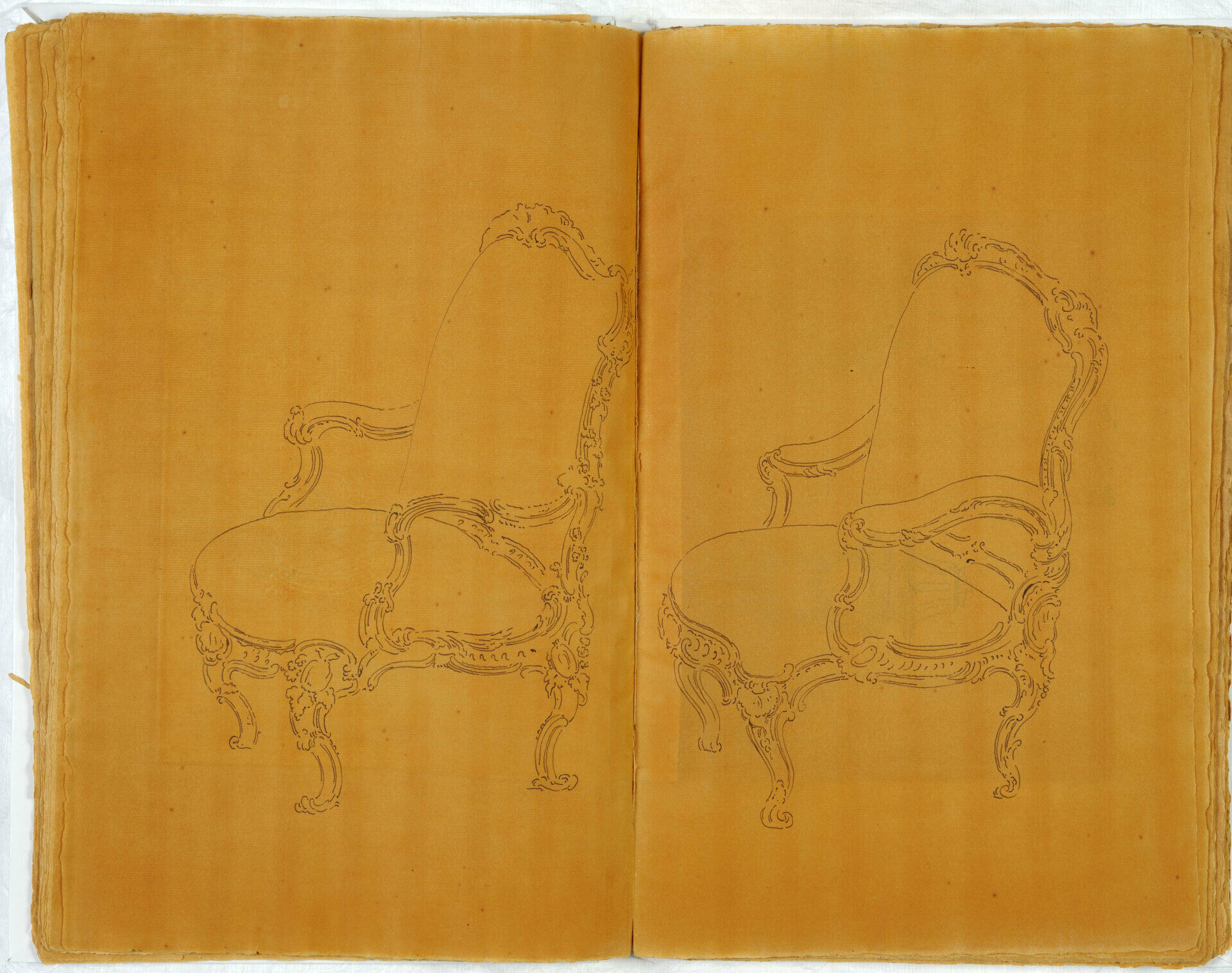

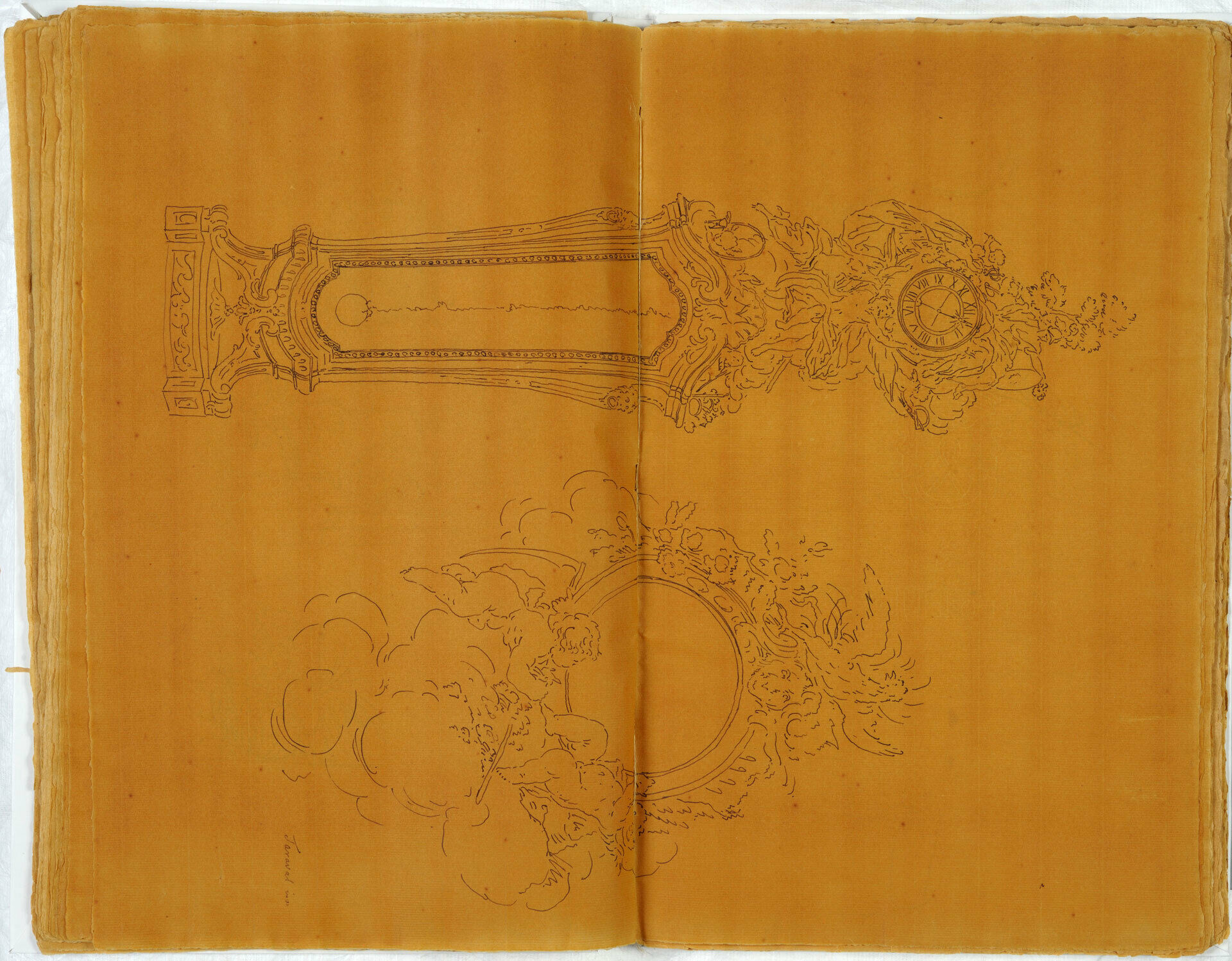

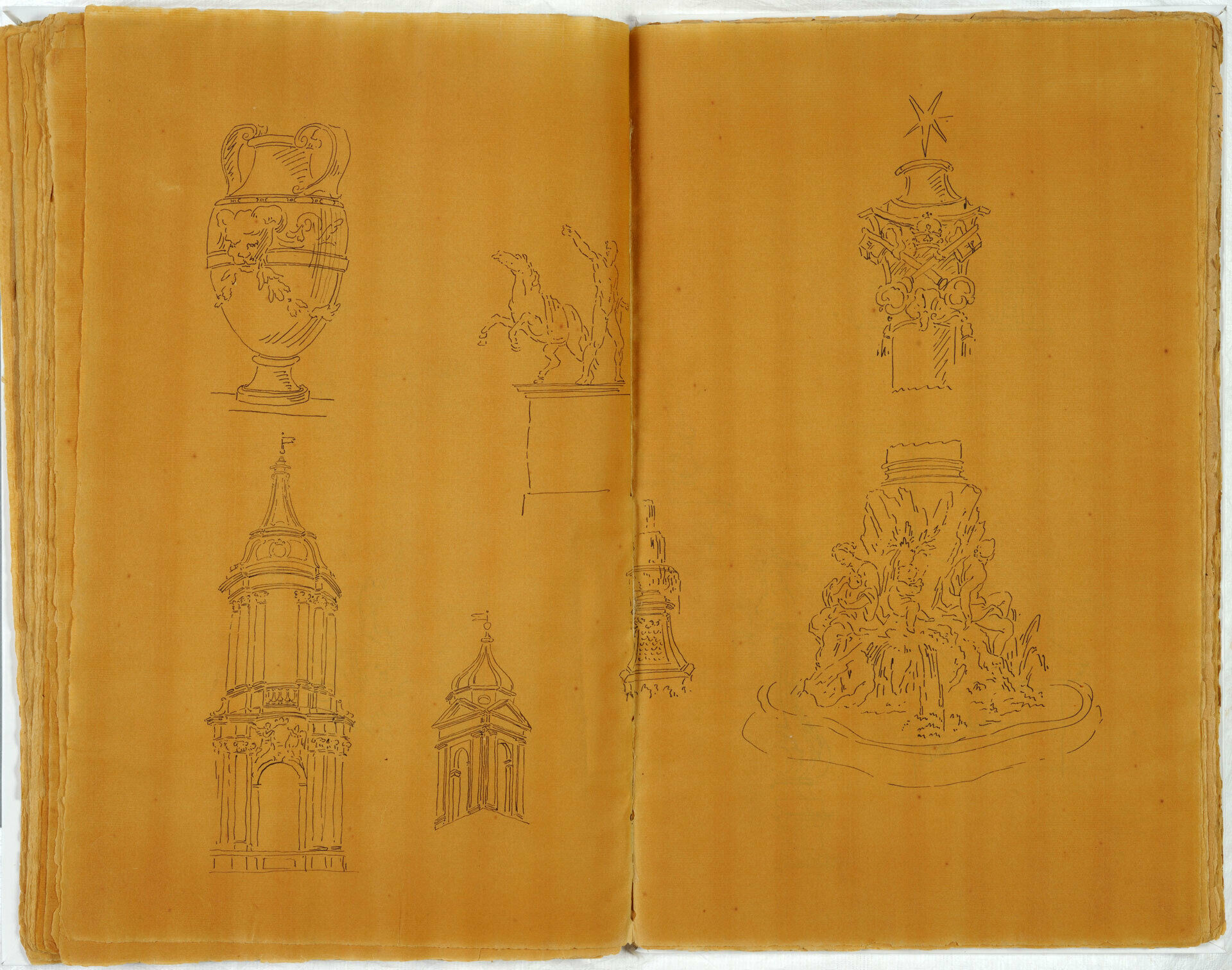

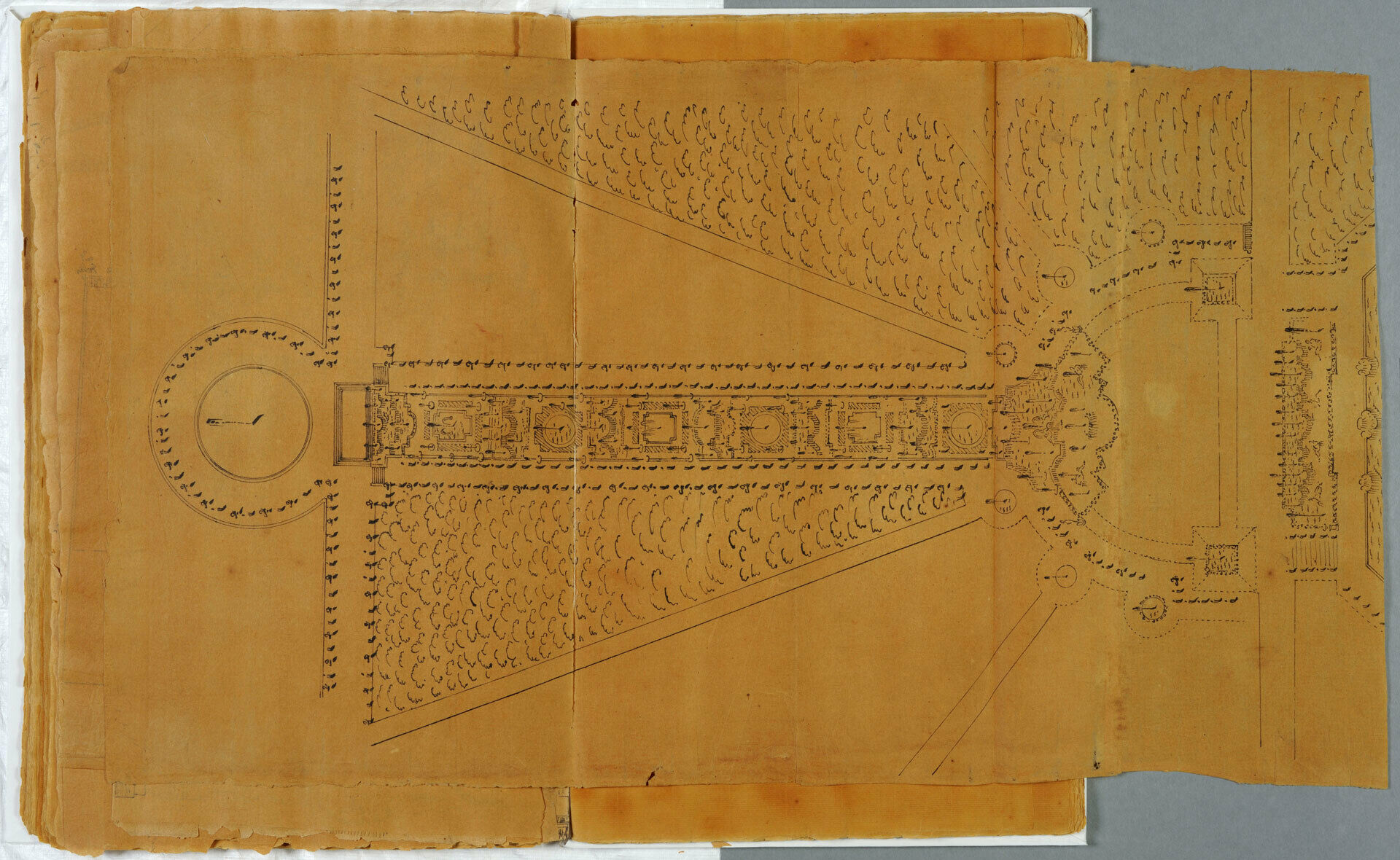

In Hårleman’s and Cronstedt’s studios, tracing paper was used to copy a large variety of subjects such as plans, elevations, and sections of residential and religious buildings, architectural elements, interior decor, sculpture, antiquities, furniture, garden designs, fountains, infrastructure, coaches, and theatrical sets and costumes.

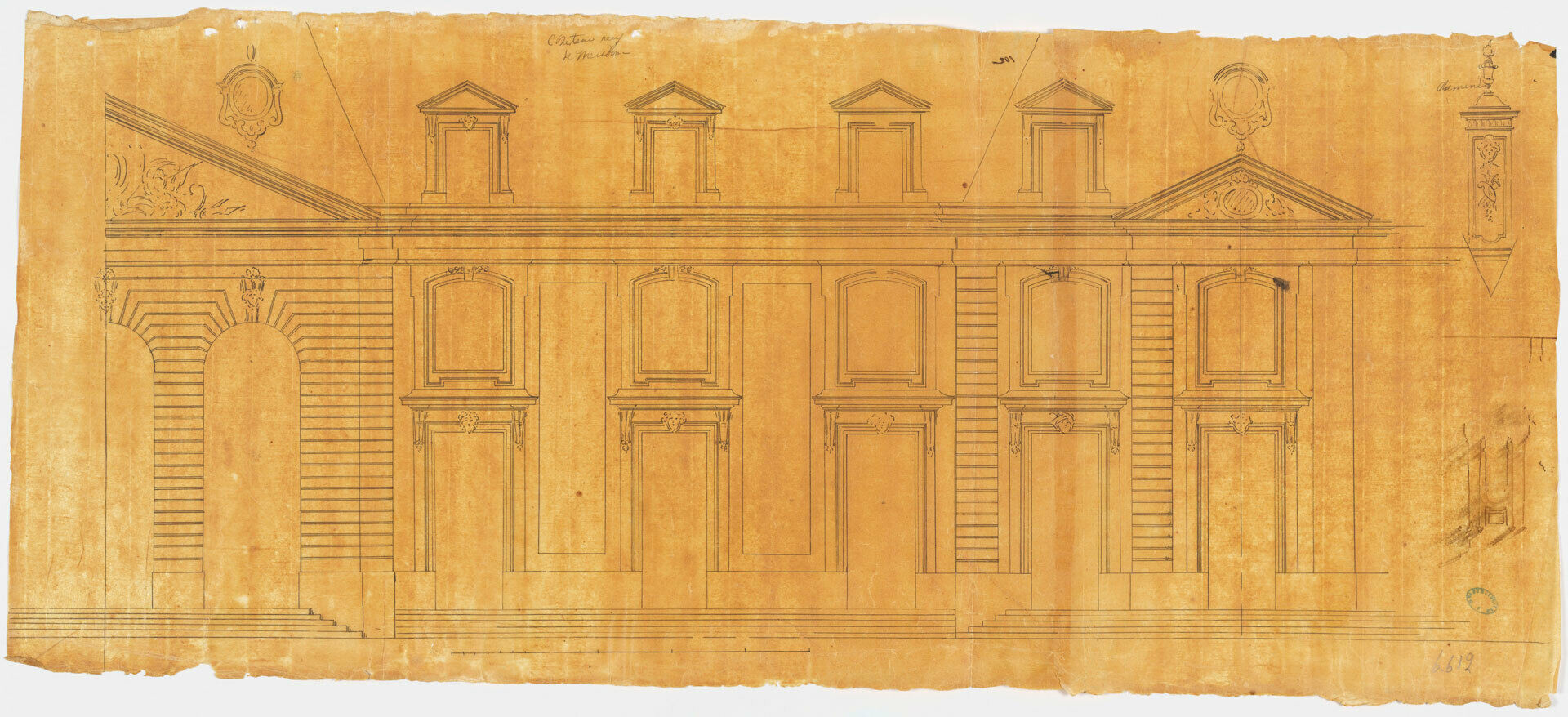

Carl Hårleman (1700–1753) after Jules Hardouin-Mansart, Château neuf, Meudon, partial elevation of the façade. Pen and black ink on two joined sheets of tracing paper, 35 × 81.1 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH THC 6612.

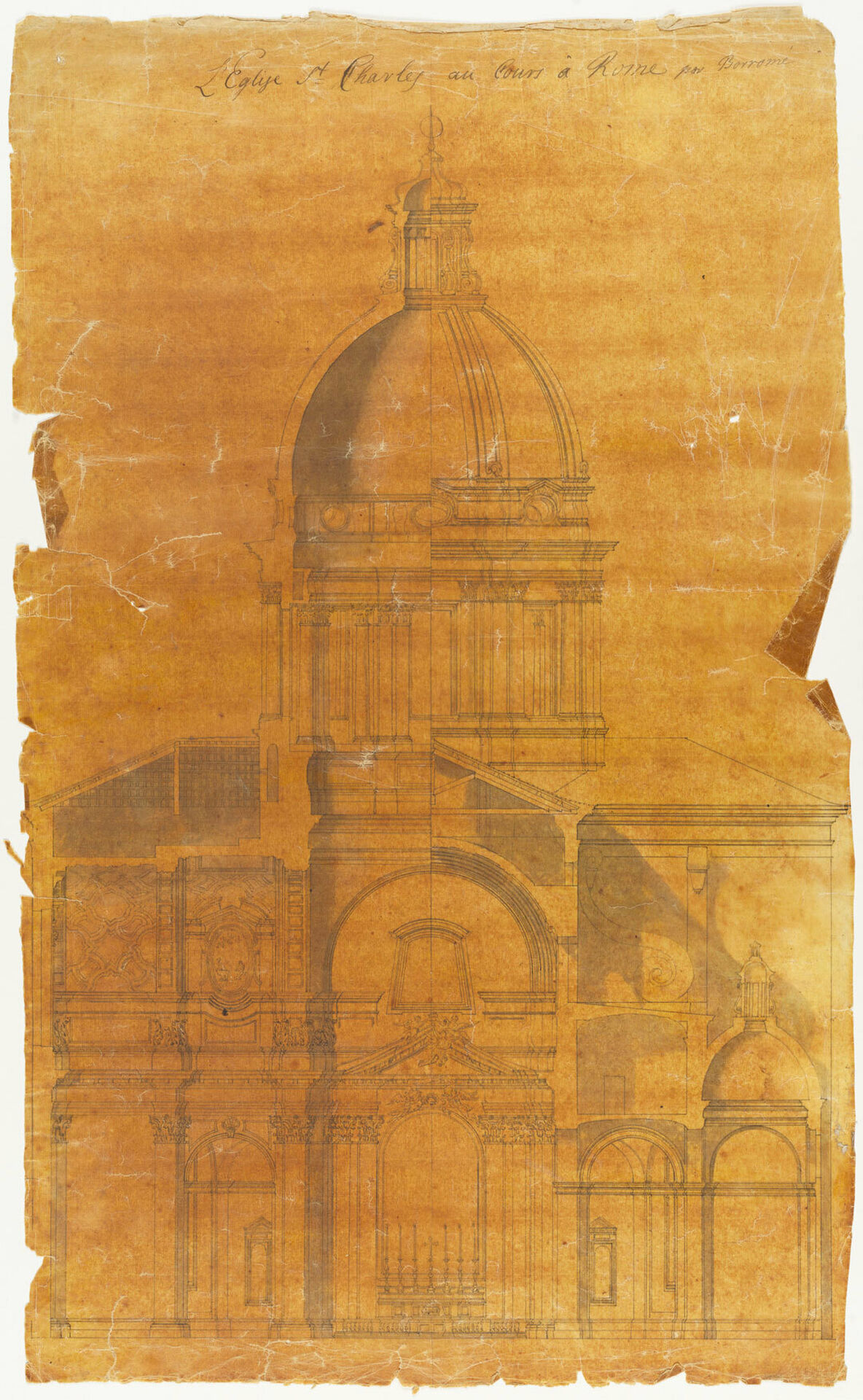

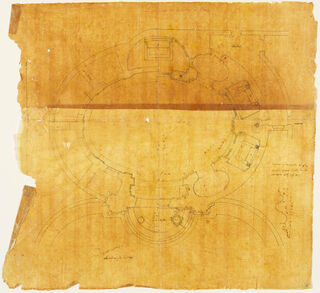

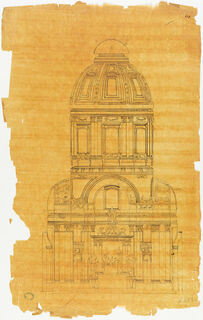

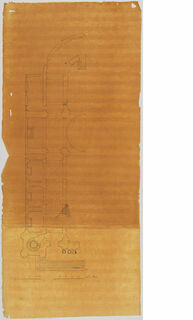

Carl Johan Cronstedt (1709–1777), Santi Ambrogio e Carlo al Corso, Rome, 1735, plan, two levels. Pen and black ink, brush and black wash on tracing paper, 63.3 × 34.4 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH A CC 292.

Carl Johan Cronstedt (1709–1777), Santi Ambrogio e Carlo al Corso, Rome, split cross-section through the transept, elevation. Pen and black ink, brush and black wash on tracing paper, 56.3 × 34.1 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH A CC 293.

The techniques and paper

Pen and ink was the most common drawing technique, even though black and red chalk and graphite also occurred as drawing media. Sometimes, brush and ink wash were used to convey the three-dimensionality of the design and indicate wall sections in structural drawings.

The tracings in the Nationalmuseum collections are often large (c.55 × 35 cm), even if tracings drawn on smaller pieces of paper and on two or more sheets glued or sewn together are not unknown. An examination of the watermarks shows that Cronstedt’s studio preferred a white laid paper produced by the Dutch manufacturer Cornelis & Jan Honig. The exceptional thinness and uniformity of this paper, once coated, helped achieve a high degree of transparency. To better handle the tracings and avoid tears, several of them have larger sheets of thick, rough paper as backing paper.

Analyses of the lipid composition of six paper samples taken from three tracings in the Tessin–Hårleman collection and three tracings in the Cronstedt collection indicate that Swedish architects had no preferred medium for making paper transparent. They used whatever substances they had in the workshop, including linseed oil, walnut oil, oil of turpentine, and a mixture of walnut and turpentine oils.

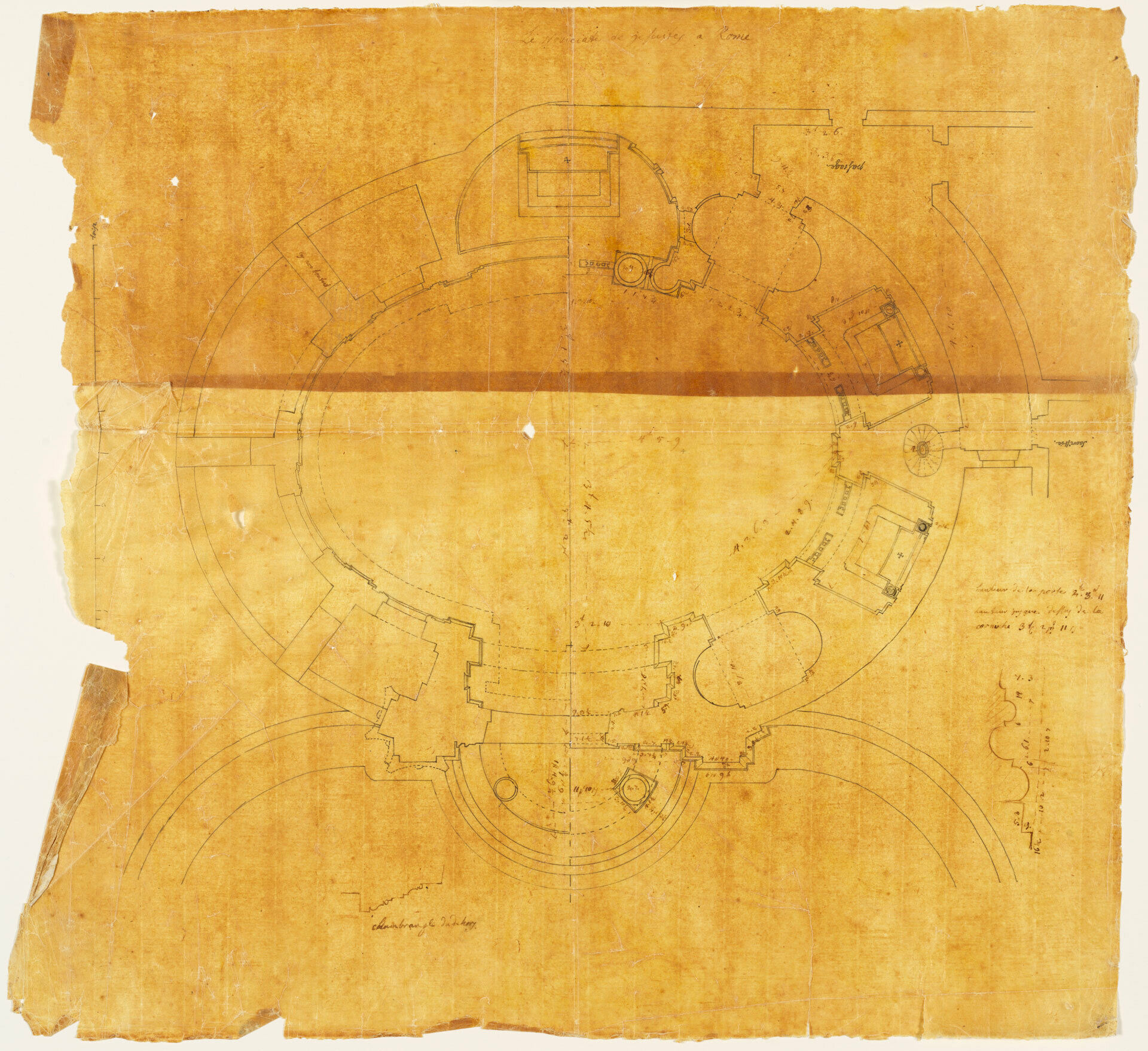

Carl Johan Cronstedt (1709–1777) after Augustin-Charles d’Aviler, Sant’Andrea al Quirinale, Rome, plans of two levels and some details. Pen and black ink on two joined sheets of tracing paper, 51.5 × 55.5 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH A CC 320.

Carl Johan Cronstedt (1709–1777), Draft for a tympanum decoration with an empty escutcheon below a lion’s head. Red chalk and white heightening on tracing paper, 19.6 × 34.5 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH A CC 36.

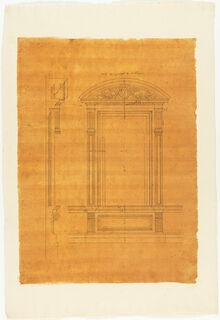

Carl Johan Cronstedt (1709–1777), Measured drawing of a niche on the façade of St Peter’s Church, Rome, elevation and profile. Pen and black ink on tracing paper laid onto a sheet of thick rag paper, 44 × 32 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH A CC 283.

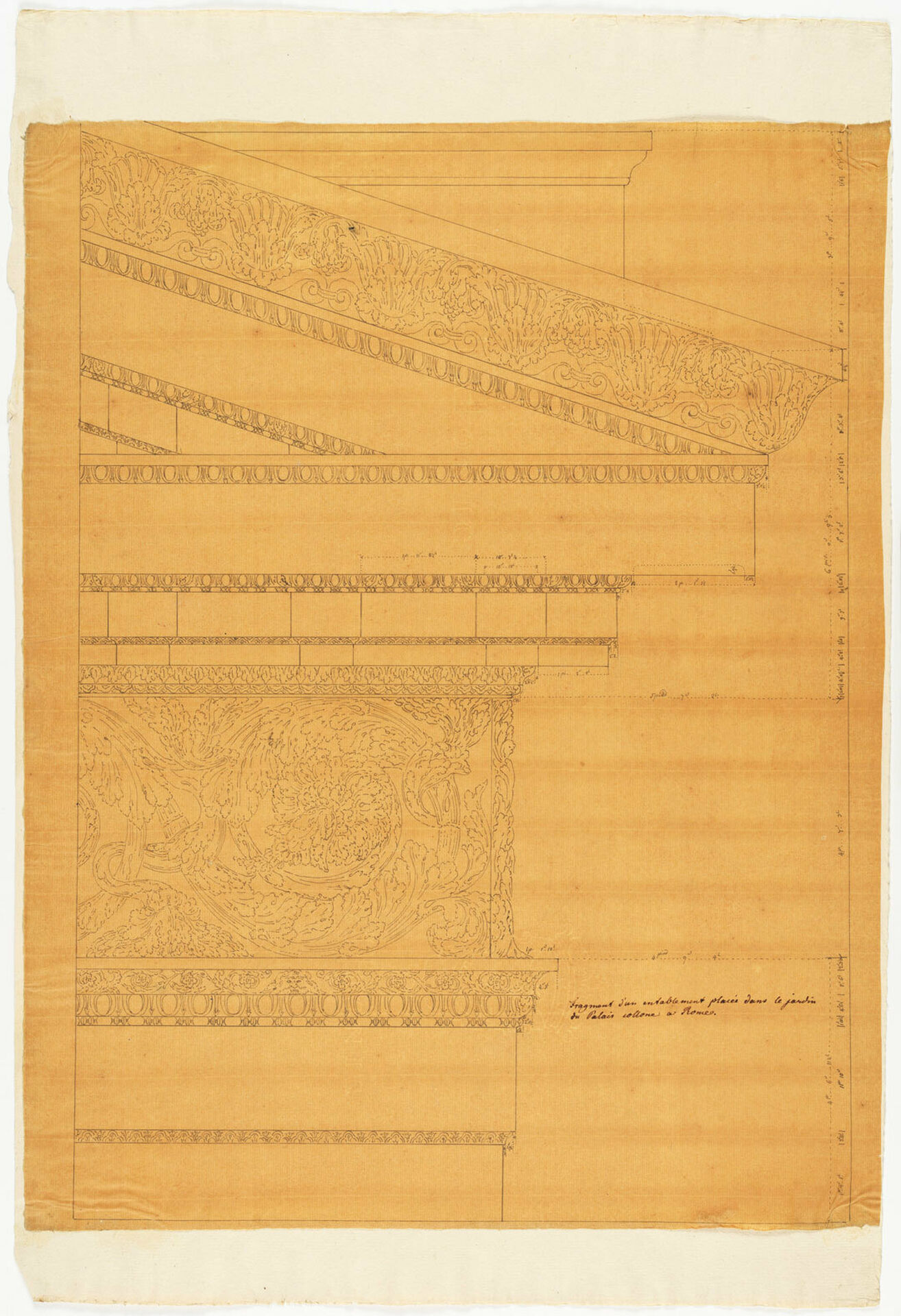

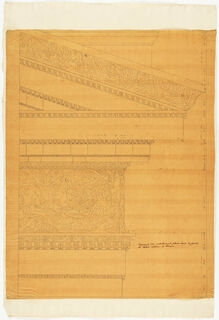

Carl Johan Cronstedt (1709–1777), Corinthian entablature and corner of a pediment from the garden of the Palazzo Colonna, Rome, profile elevation. Pen and black ink on tracing paper laid onto a sheet of thick rag paper, 48.5 × 37.7. Nationalmuseum NMH A CC 360.

Function and use

Several of Carl Hårleman’s tracings were done from drawings by prominent French seventeenth- and eighteenth-century architects such as André Le Nôtre, Jules Hardouin-Mansart, and Robert de Cotte and by French masters of interior decoration such as François-Antoine Vassé and Gilles-Marie Oppenord. It is likely that Hårleman had traced some of their drawings when he was studying in Paris between 1721 and 1725. However, many tracings may also have been done in the Stockholm workshop from drawings by the same masters brought there from France, as suggested by the presence of numerous originals in the Nationalmuseum collections.

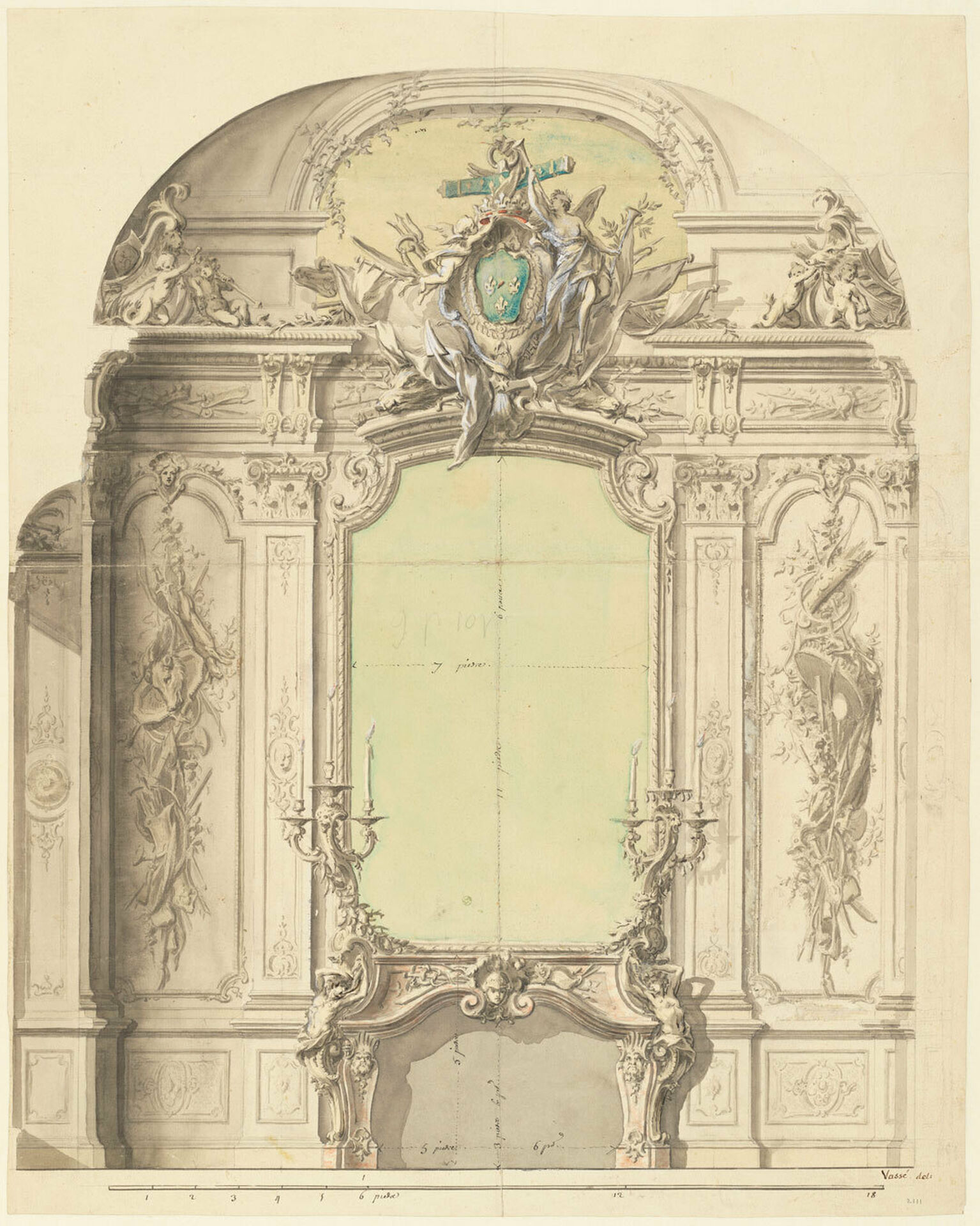

François-Antoine Vassé (1681–1736), Hôtel de Toulouse, Paris, study for a chimney piece at the far end of the Galerie Dorée, c.1713–1718. Graphite, pen and black ink, watercolour, traces of pricking, 60.2 × 48.1 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH THC 2111.

The traced copy by Carl Hårleman, superimposed on François-Antoine Vassé’s original drawing.

Carl Hårleman (1700–1753) after François-Antoine Vassé, Hôtel de Toulouse, Paris, study for a chimney piece at the far end of the Galerie Dorée, upper part. Traces of graphite, pen and black ink, brush and grey wash on tracing paper, 34.5 × 55.5 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH THC 7103.

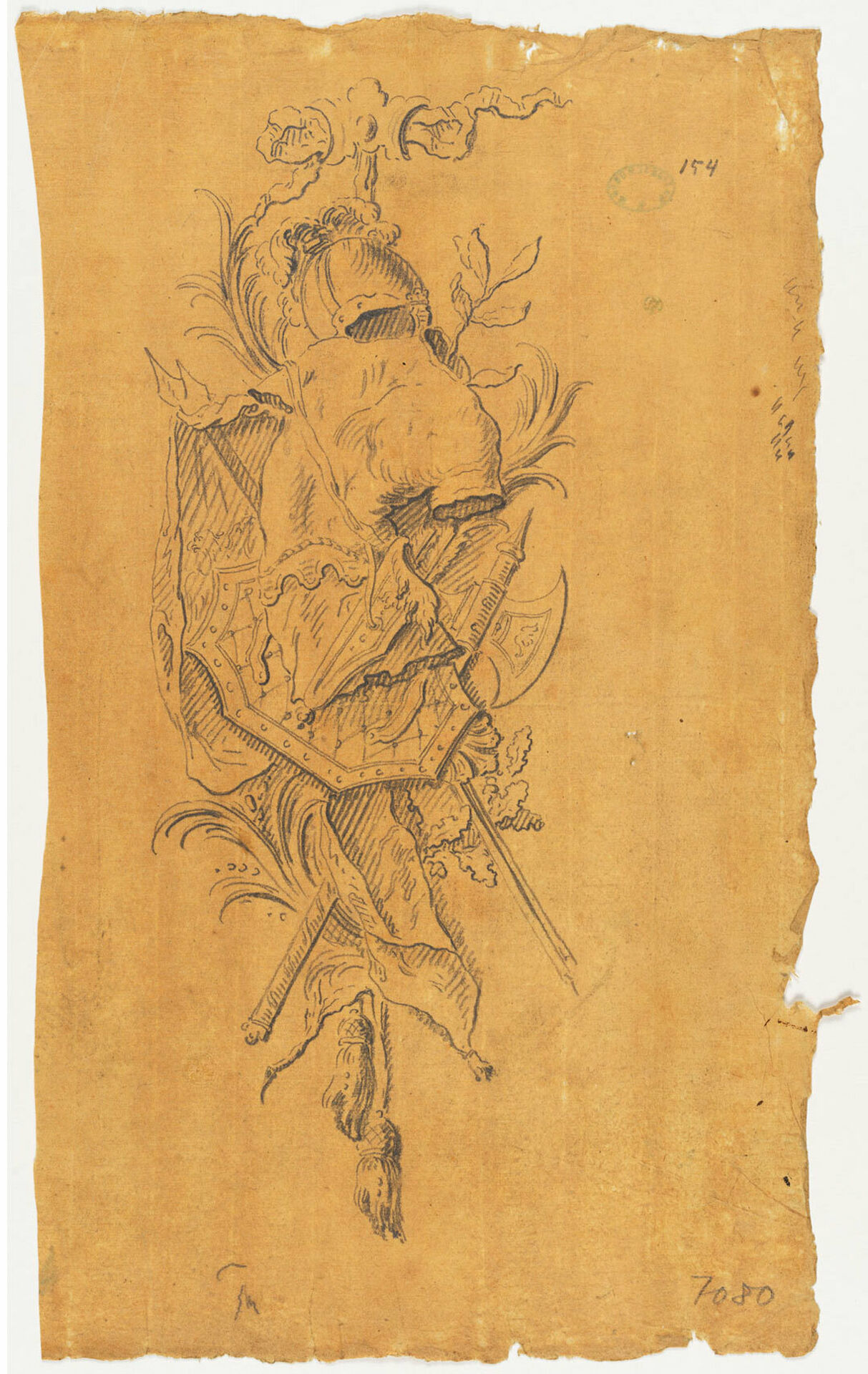

Carl Hårleman (1700–1753), Ornamental design for a trophy. Pen and dark brown ink, brush and grey wash on tracing paper, 35 × 18 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH THC 7079.

Carl Hårleman (1700–1753), Ornamental design for a trophy. Black chalk on tracing paper, 34.5 × 19.7 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH THC 7080.

It may have been Hårleman who introduced Carl Johan Cronstedt to the practice of copying with transparent paper. Cronstedt joined Hårleman’s workshop in 1730 and the following year accompanied his master to Paris, where Hårleman hoped to recruit French stuccoists for the decoration of the Royal Palace of Stockholm. It was likely while he was an apprentice that Cronstedt put together a portfolio of 73 tracings of drawings and prints in his master’s collection and the collection of Carl Gustaf Tessin (1695–1770), son of the architect Nicodemus the Younger.

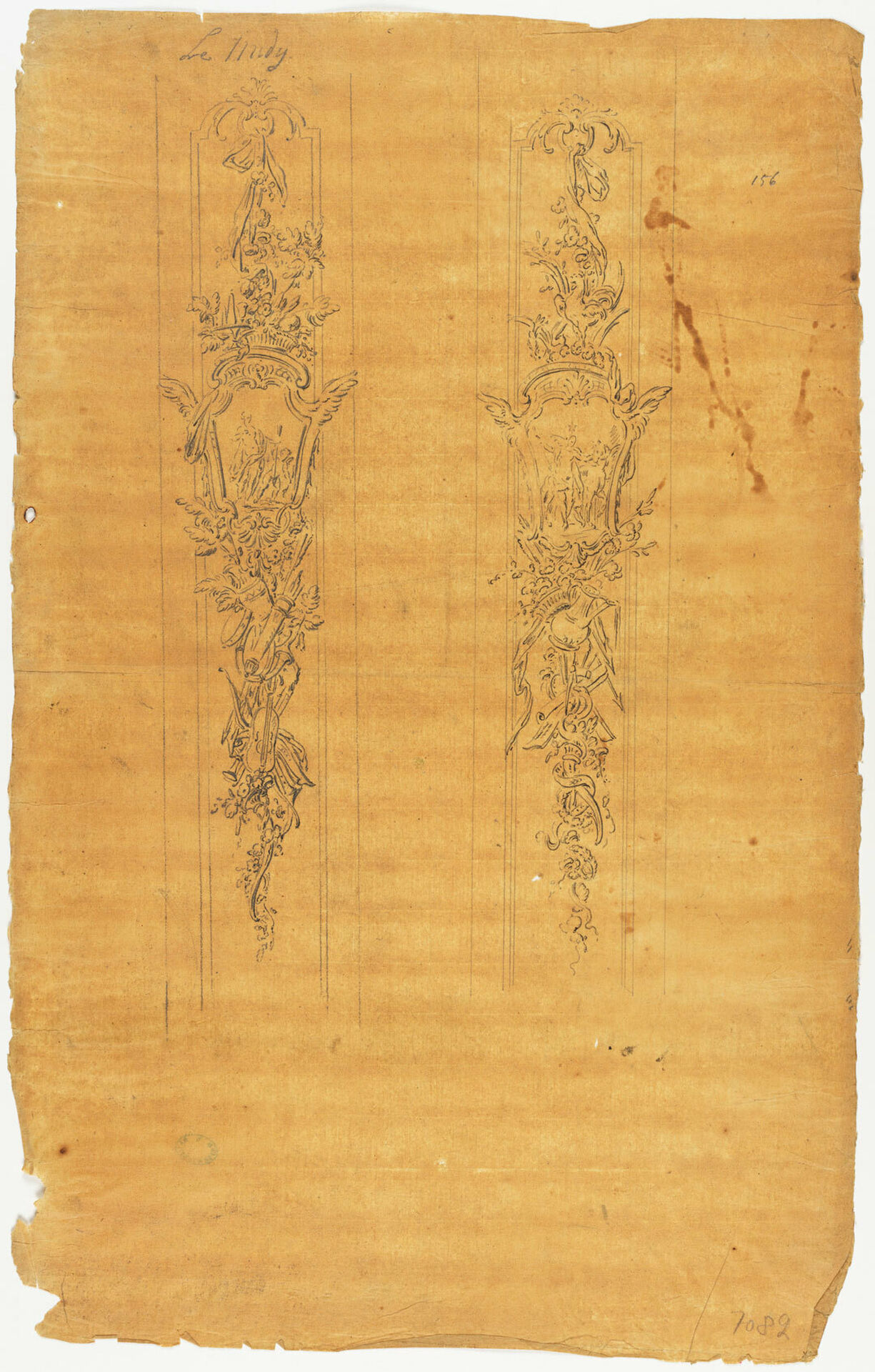

Carl Hårleman (1700–1753) after François-Antoine Vassé, Ornamental design for two wall panels. Graphite, pen and black ink on tracing paper, 54.5 × 34.5 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH THC 7082.

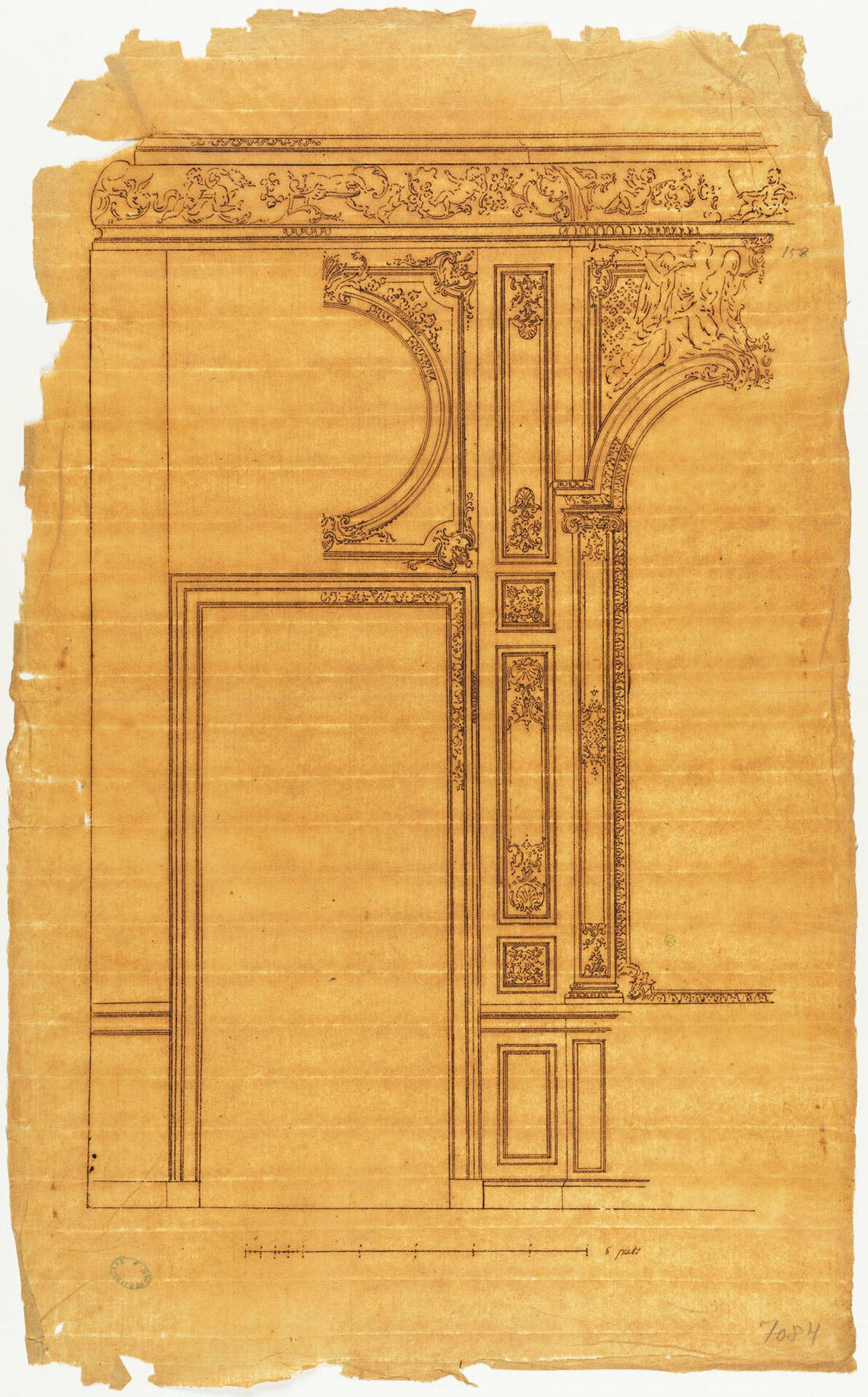

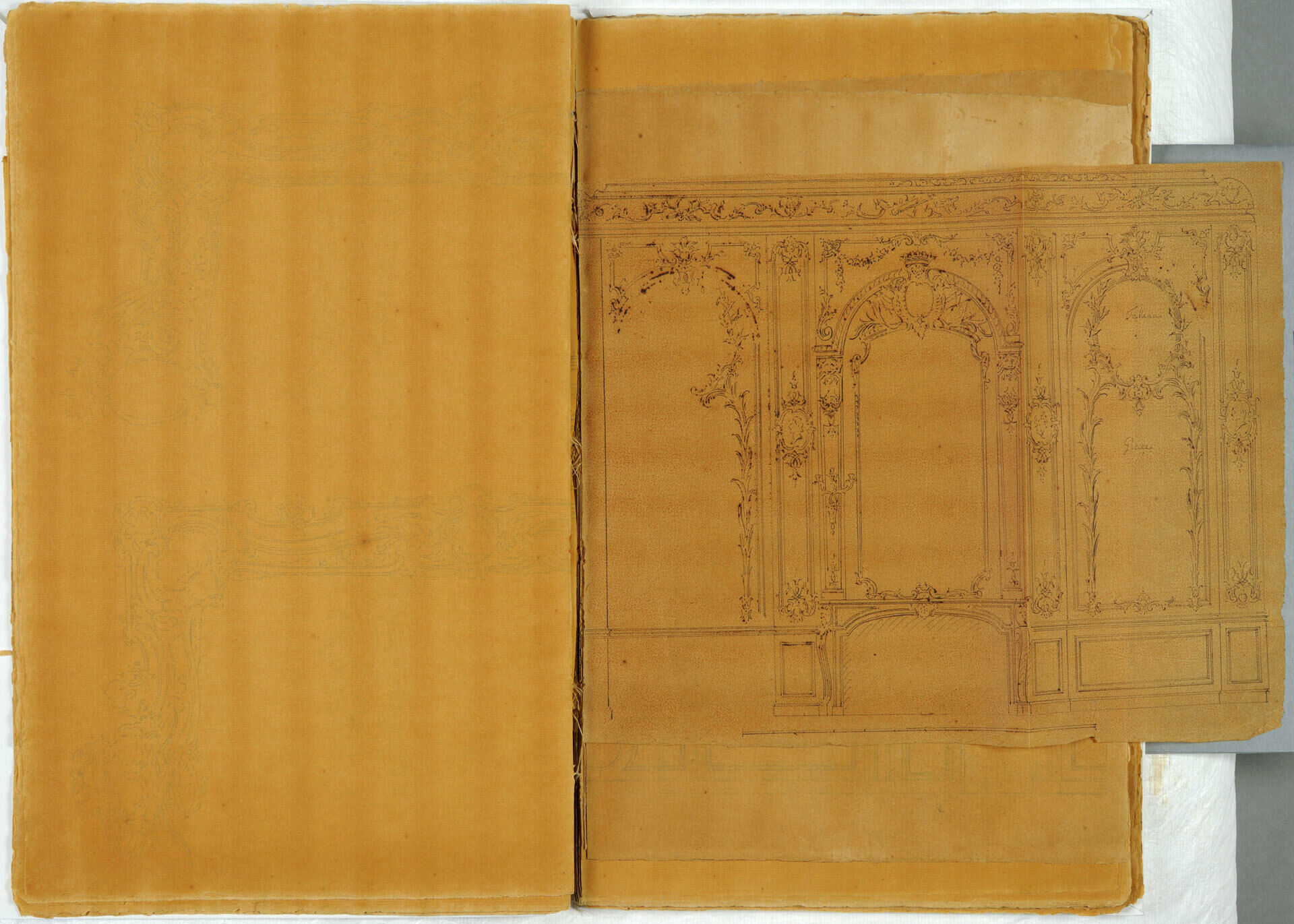

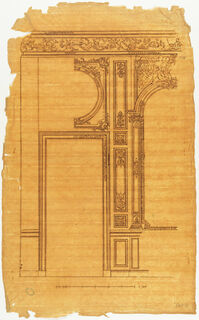

Carl Hårleman (1700–1753) after Gilles-Marie Oppenord (?), Partial elevation of a panelled interior with a door and mirror. Pen and brown ink on tracing paper, 56.5 × 34.5 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH THC 7084.

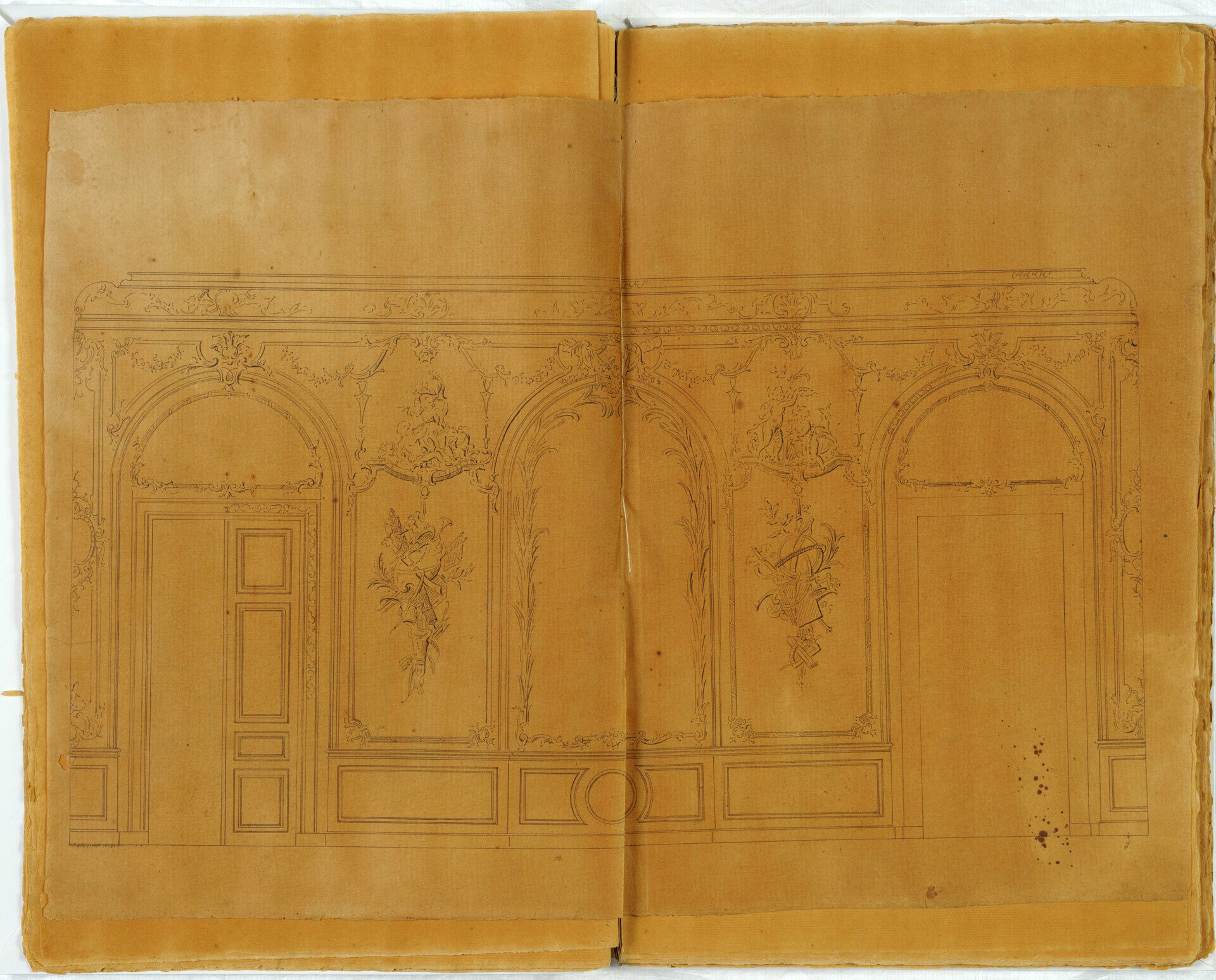

Hårleman’s tracings show that transparent paper was especially suitable for copying the extravagant and asymmetrical designs of the French rococo style. The transparency of the medium allowed them to easily trace complex originals free hand, instead of pricking them along the lines. In fact, it is likely that transparent paper was a substantial help when Hårleman wanted to make accurate copies of Vassé’s and Oppenord’s ornamentation and architectural elements, contributing to the rapid transfer and popularisation in Sweden of the French models of rococo interior decoration in the 1730s.

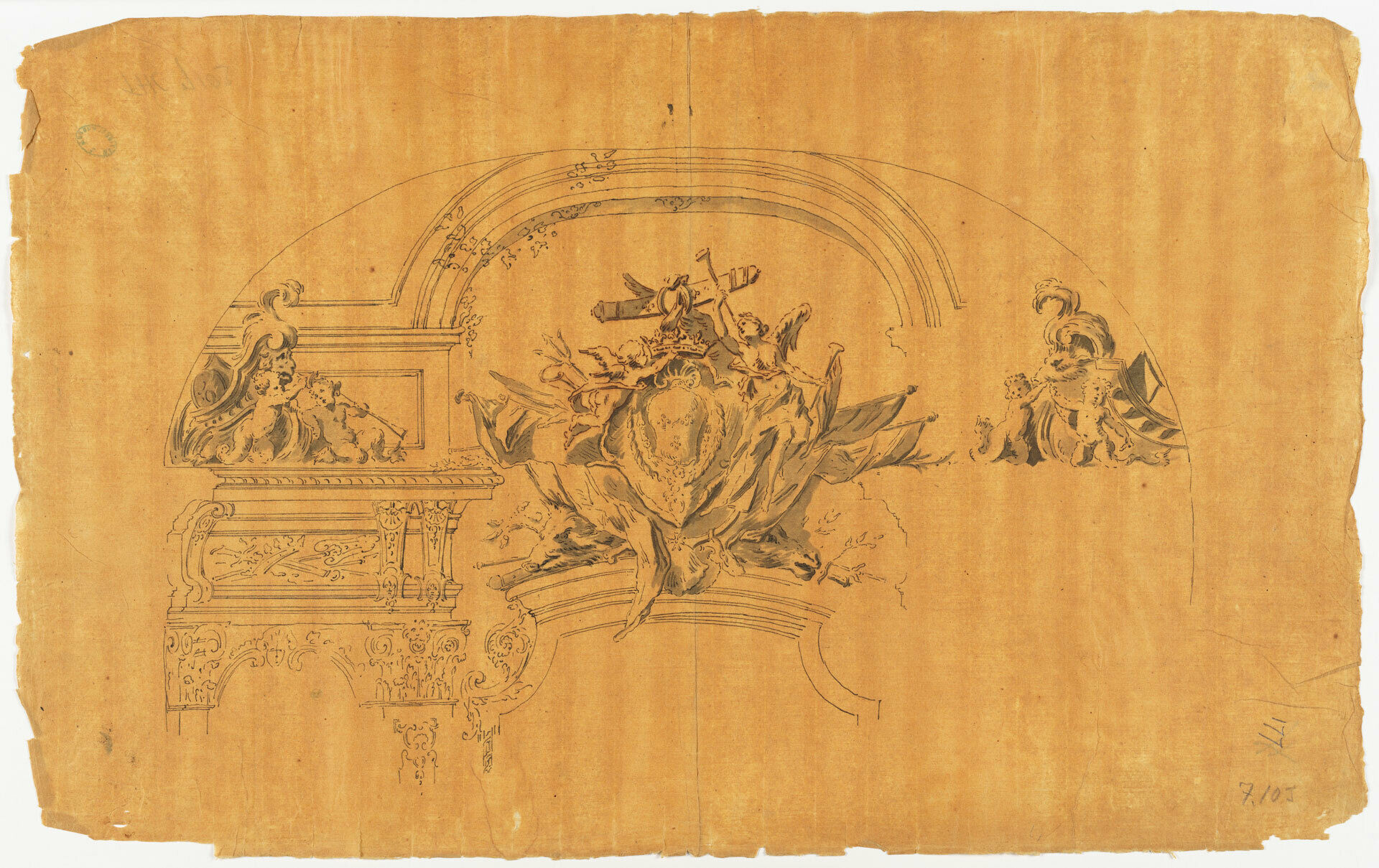

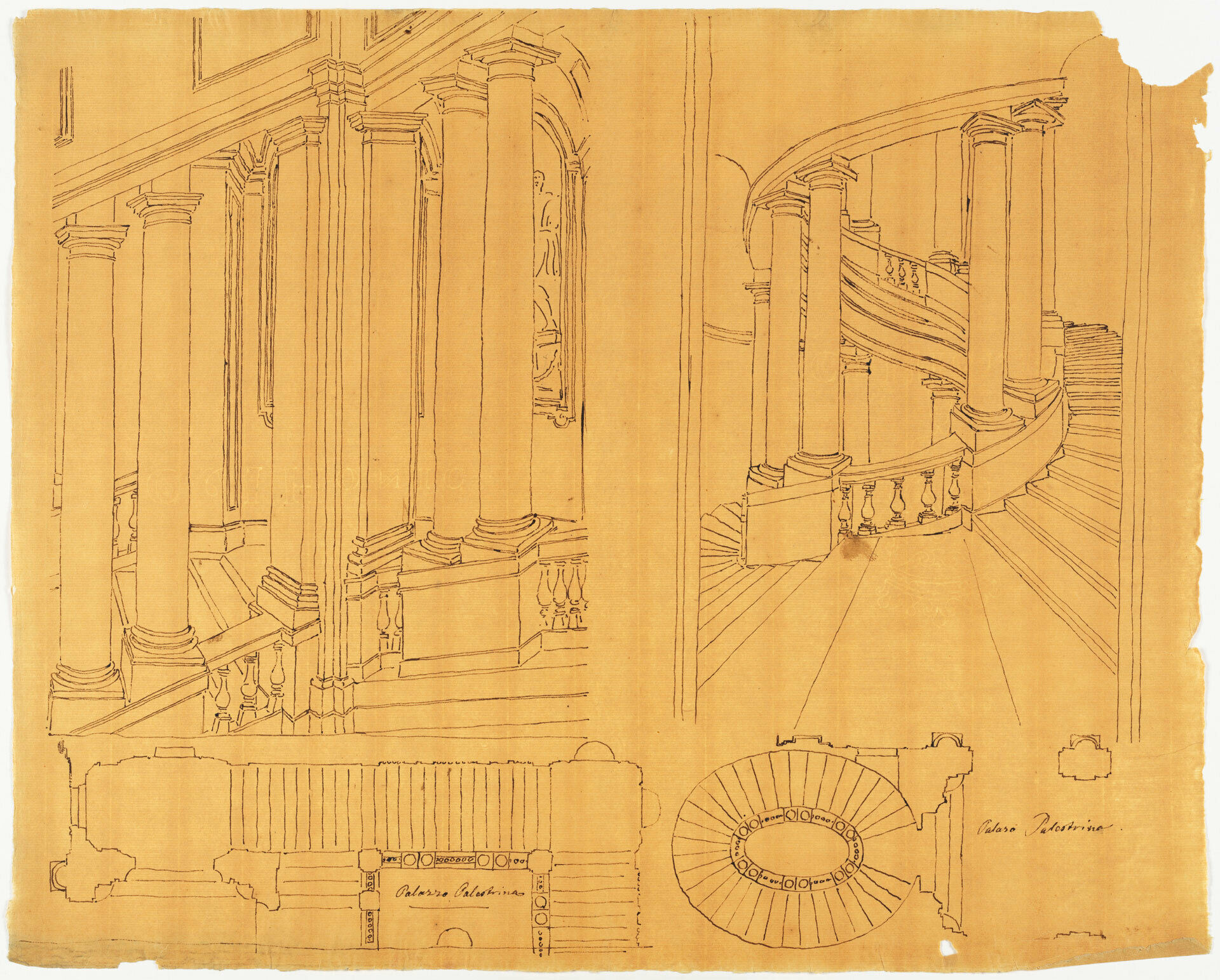

It was in this collection Carl Johan Cronstedt also traced some of Nicodemus Tessin’s own project drawings and copies of modern architecture. One tracing showed the two staircases of the Barberini Palace in Rome and combined in one sheet the drawings originally done by Tessin as separate sheets. With this solution, Cronstedt obtained an immediate visual comparison between architectural elements of the same building.

Carl Johan Cronstedt (1709–1777) after Nicodemus Tessin the Younger, The rectangular and oval staircases, Palazzo Barberini, Rome, perspective elevations and plans. Pen and black ink on tracing paper, 39 × 48.8 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH A CC 224.

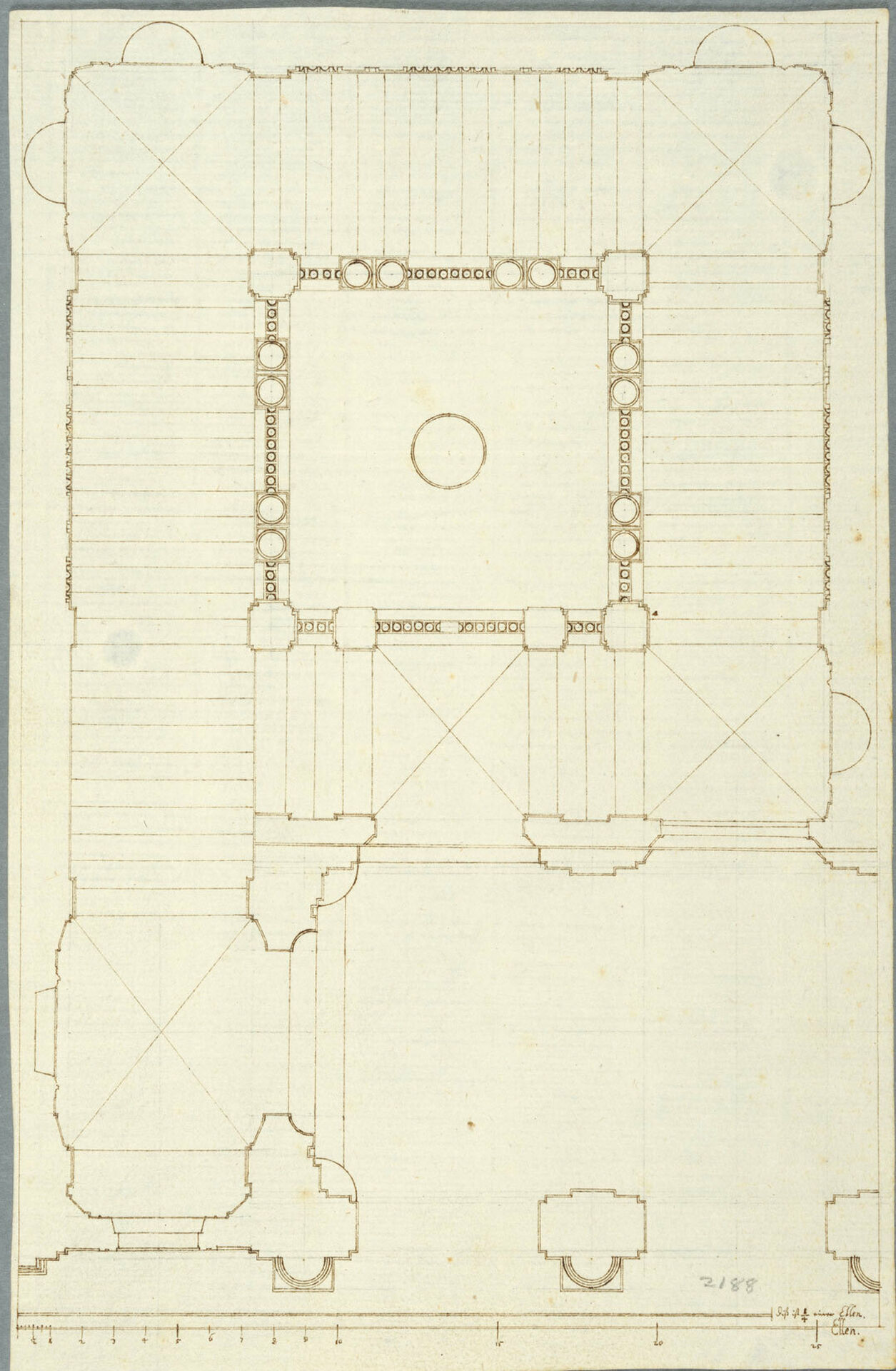

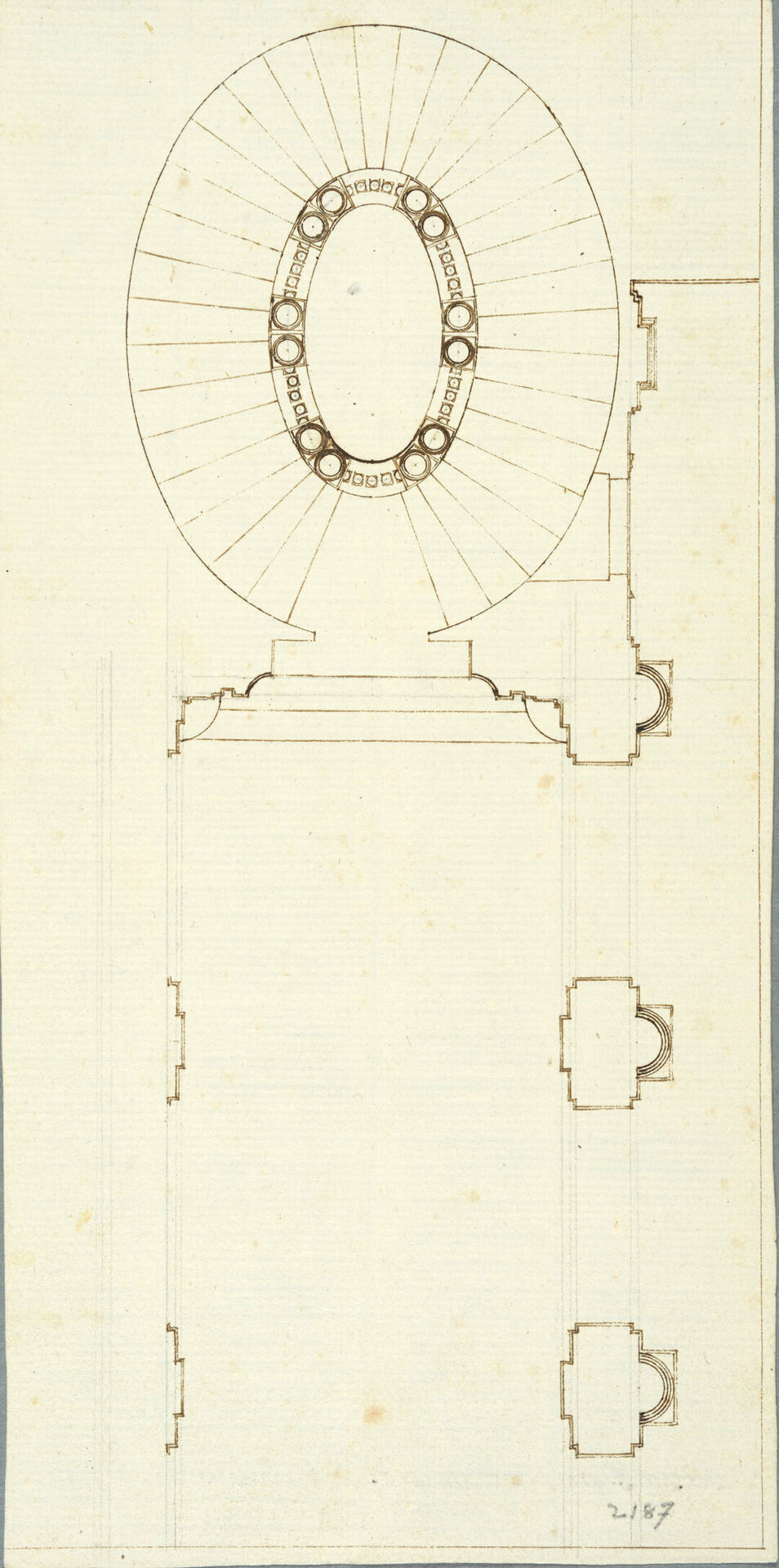

In tracing symmetrical plans and elevations, Carl Johan Cronstedt deliberately copied only half or a quarter of the original design, since, if needed, the missing part could be obtained by flipping the sheet. This praxis shows that Cronstedt now appreciated the possibilities of transparent paper as a copying medium, and especially the speed and effortlessness of tracing.

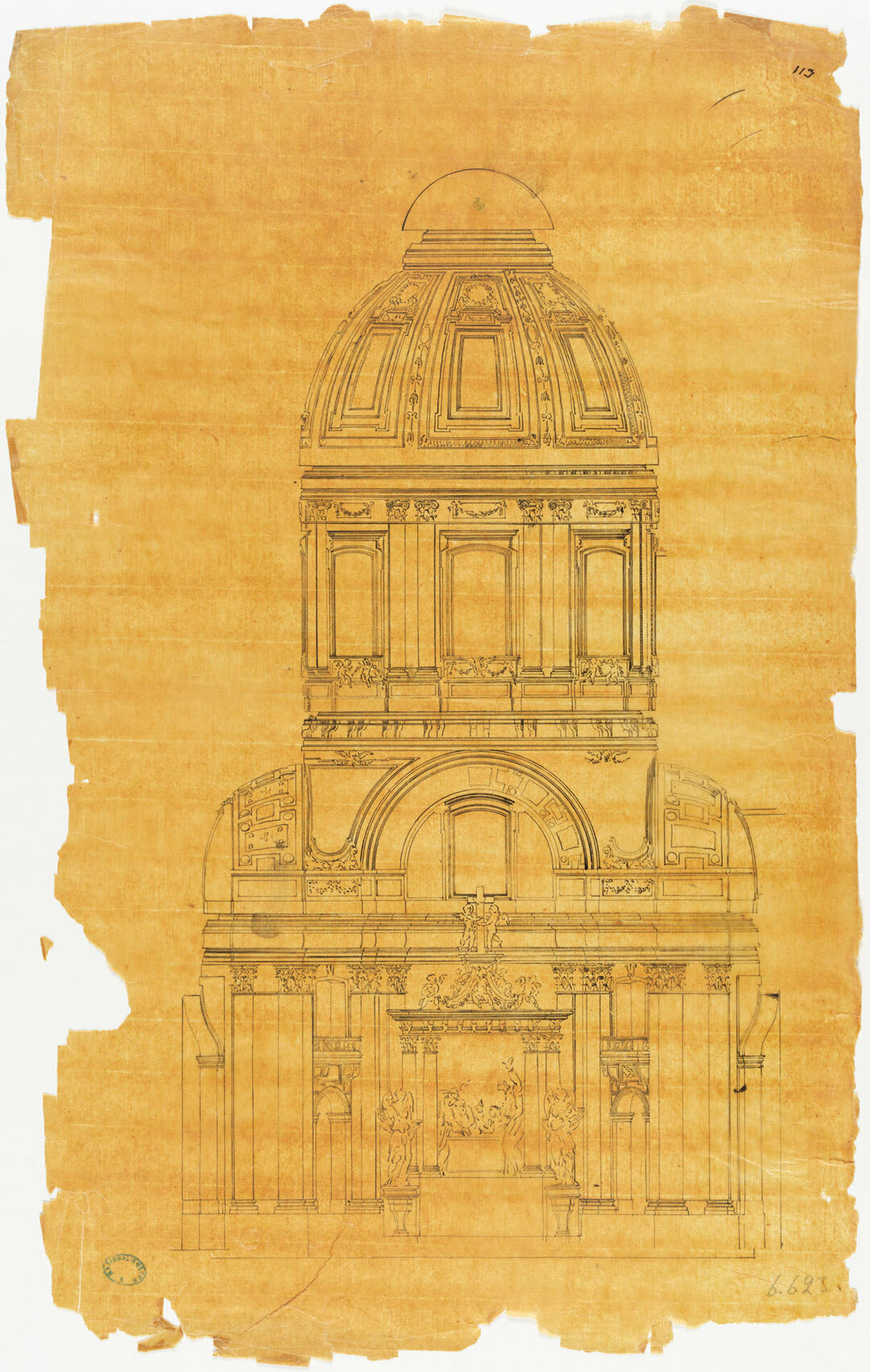

Carl Hårleman (1700–1753) after Gilles-Marie Oppenord (?), Saint-Sulpice, Paris, section of the transept towards the altar. Pen and black ink on tracing paper, 54 × 34.5 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH THC 6623.

Carl Johan Cronstedt (1709–1777) after Carl Hårleman, Saint-Sulpice, Paris, section of the transept towards the altar, right half. Pen and black ink on tracing paper, 51.1 × 34.6 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH A CC 138.

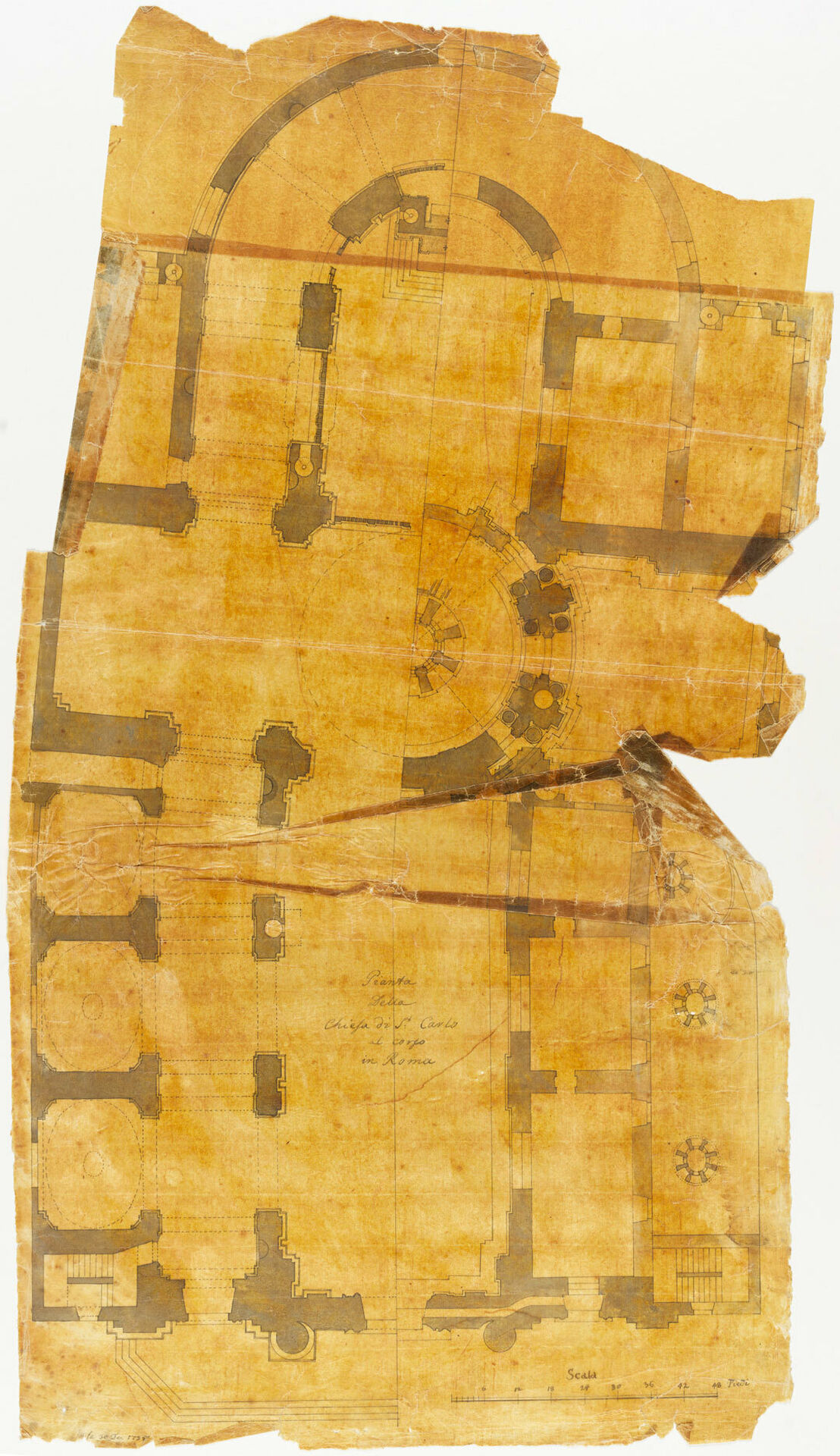

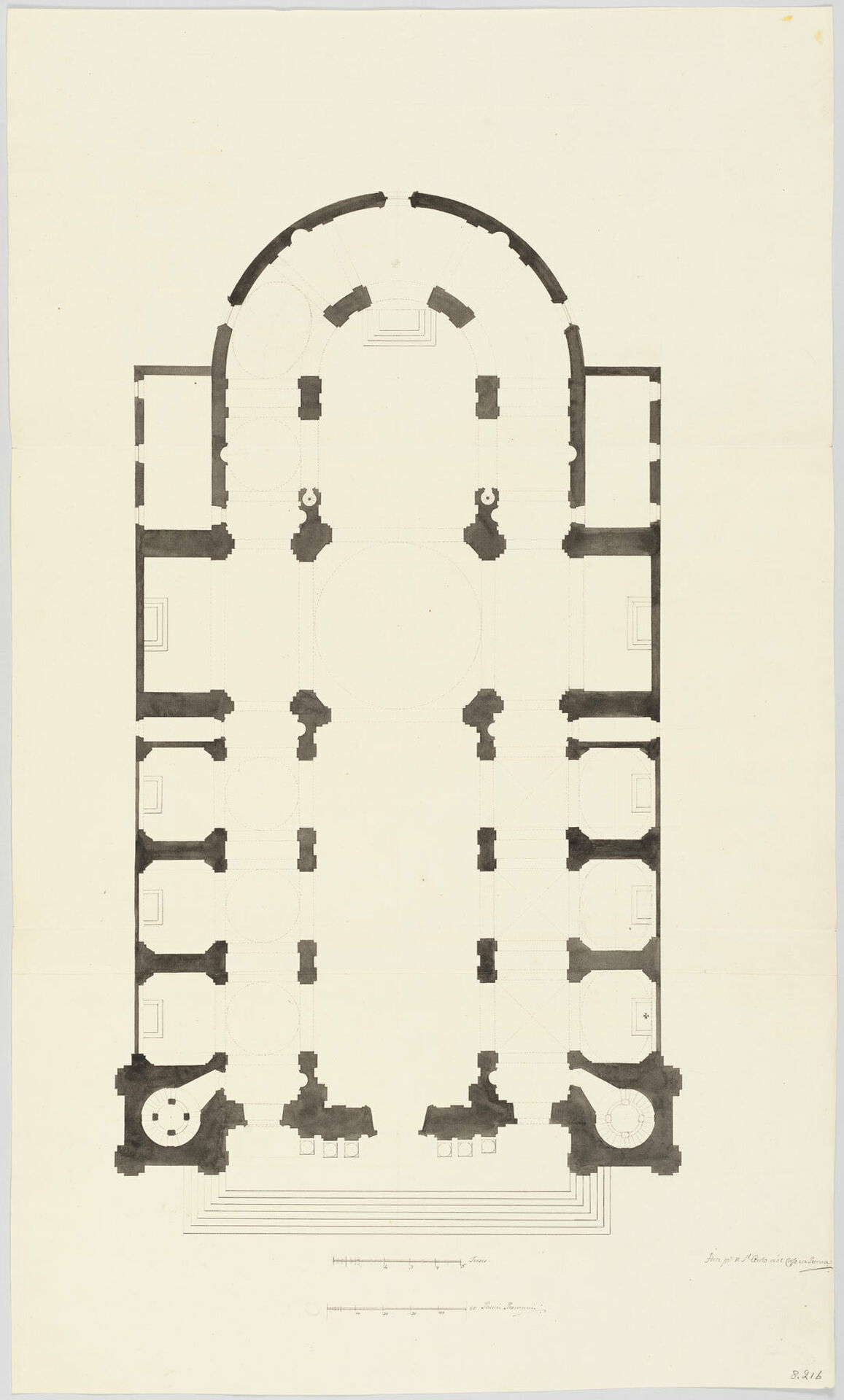

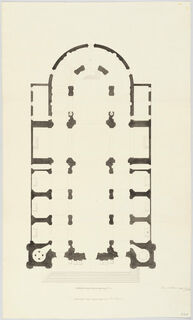

Carl Hårleman (1700–1753) after Martino Longhi the Younger (?), Plan for Santi Carlo e Ambrogio al Corso, Rome. Pen and black ink over graphite, brush and black wash on two joined sheets of white laid paper, traces of pricking, 77.7 × 46.2 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH THC 8216.

Carl Johan Cronstedt (1709–1777) after Carl Hårleman, Plan for Santi Ambrogio e Carlo al Corso, Rome, left half. Pen and black ink on two joined sheets of tracing paper, 79 × 34.4 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH A CC 183.

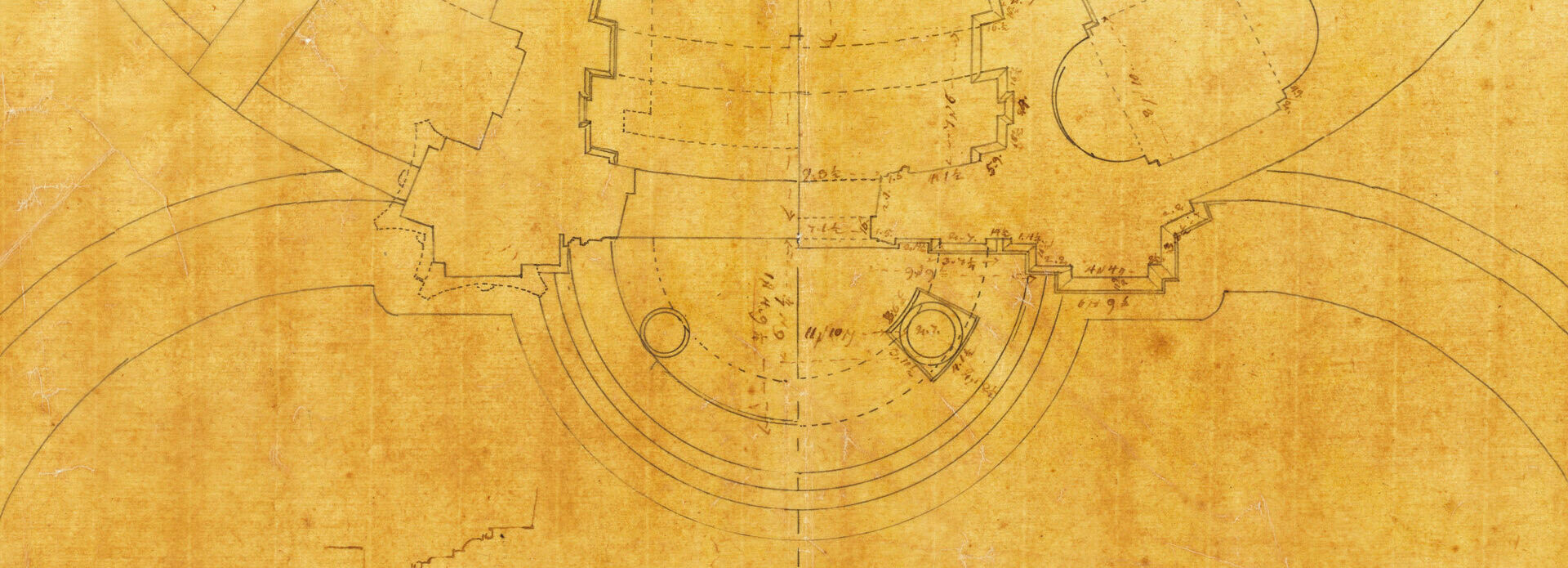

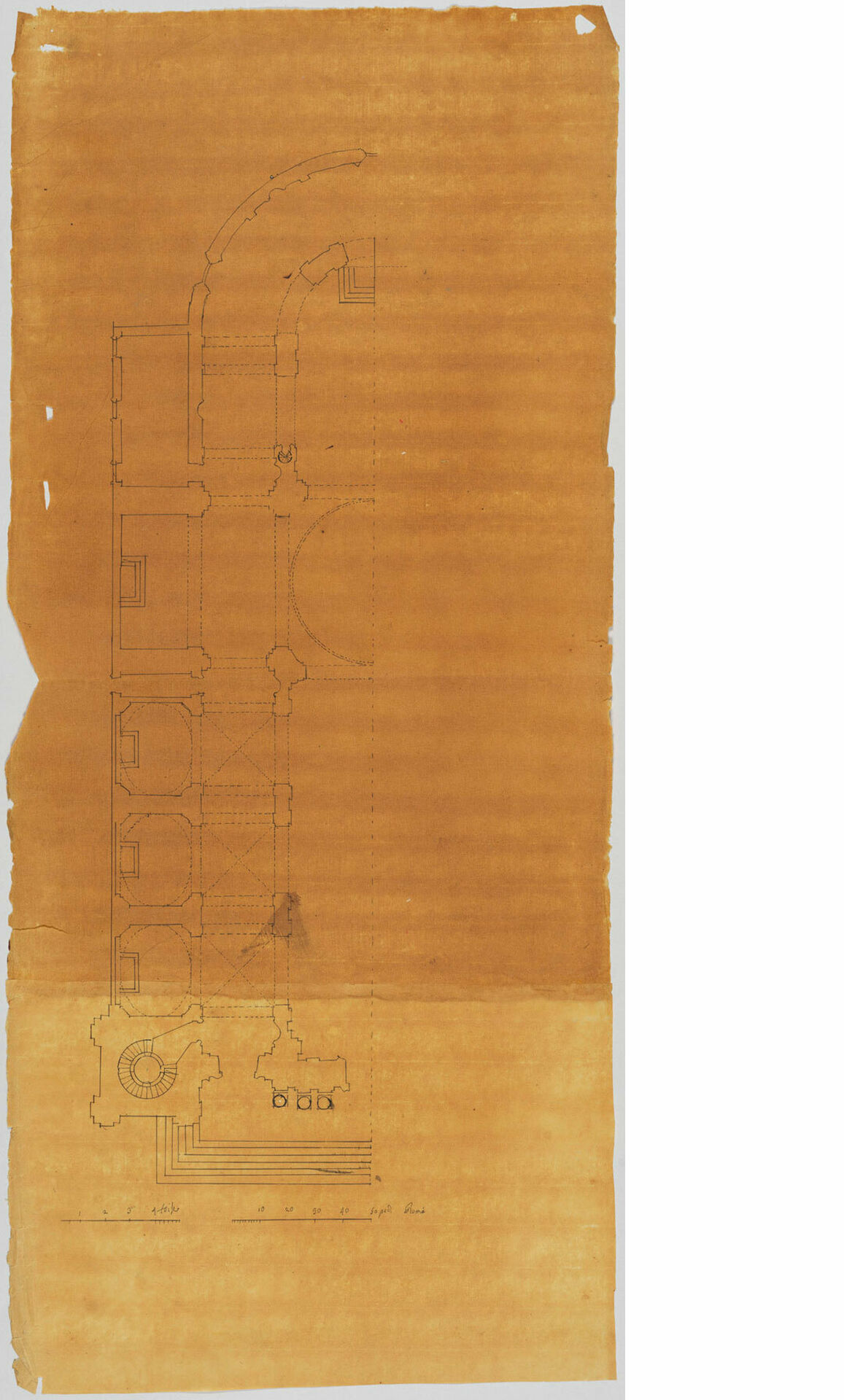

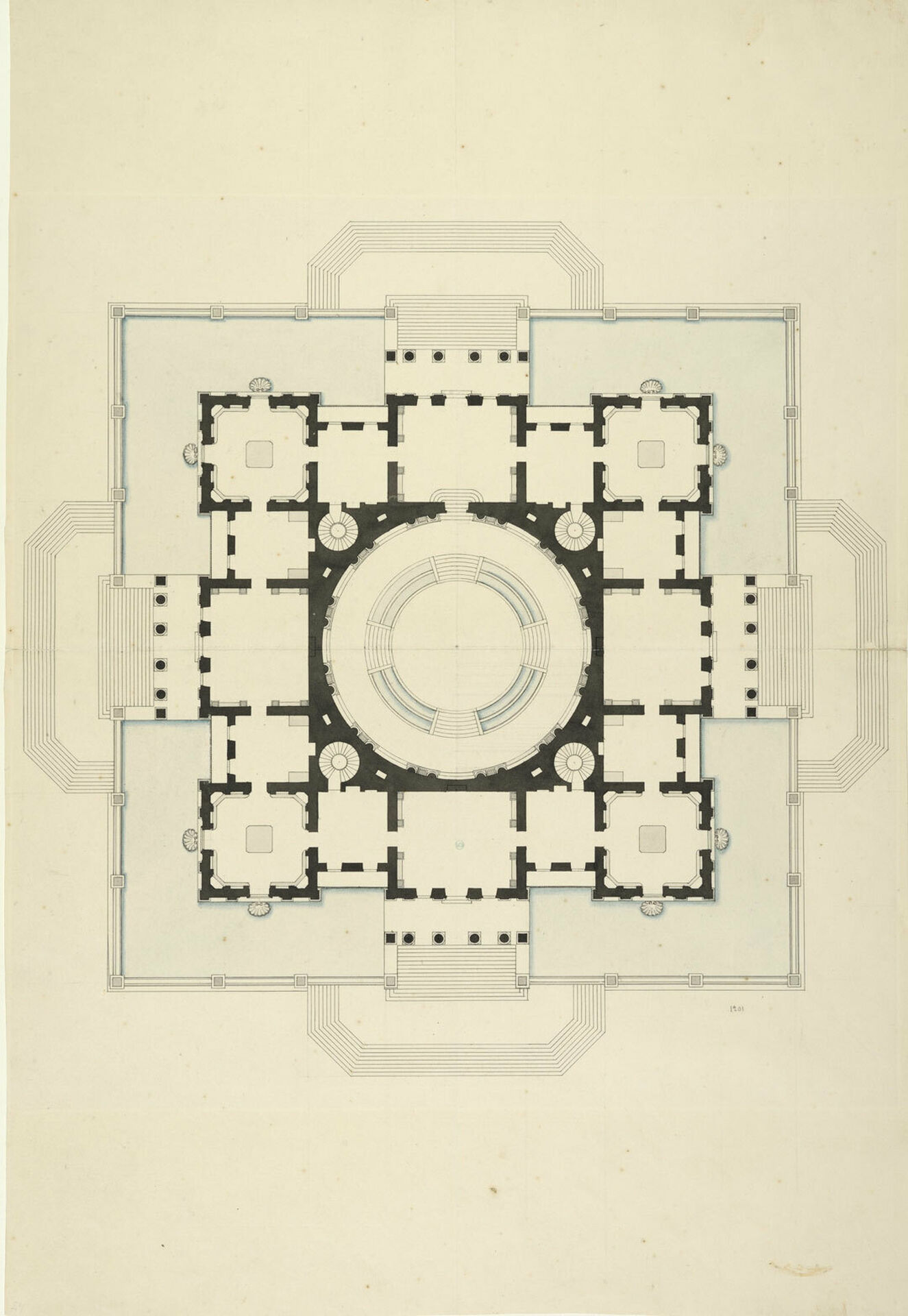

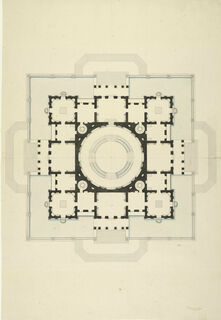

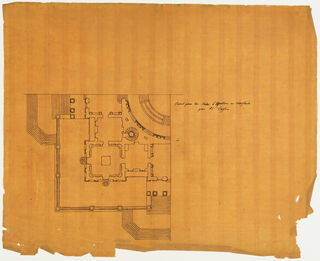

Gustaf Palmcrantz (1694–1715) after Nicodemus Tessin the Younger, Plan for a Temple of Apollo at Versailles. Pen and black ink over graphite, brush and black, wash on white laid paper, 68.9 × 46.7 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH THC 1201.

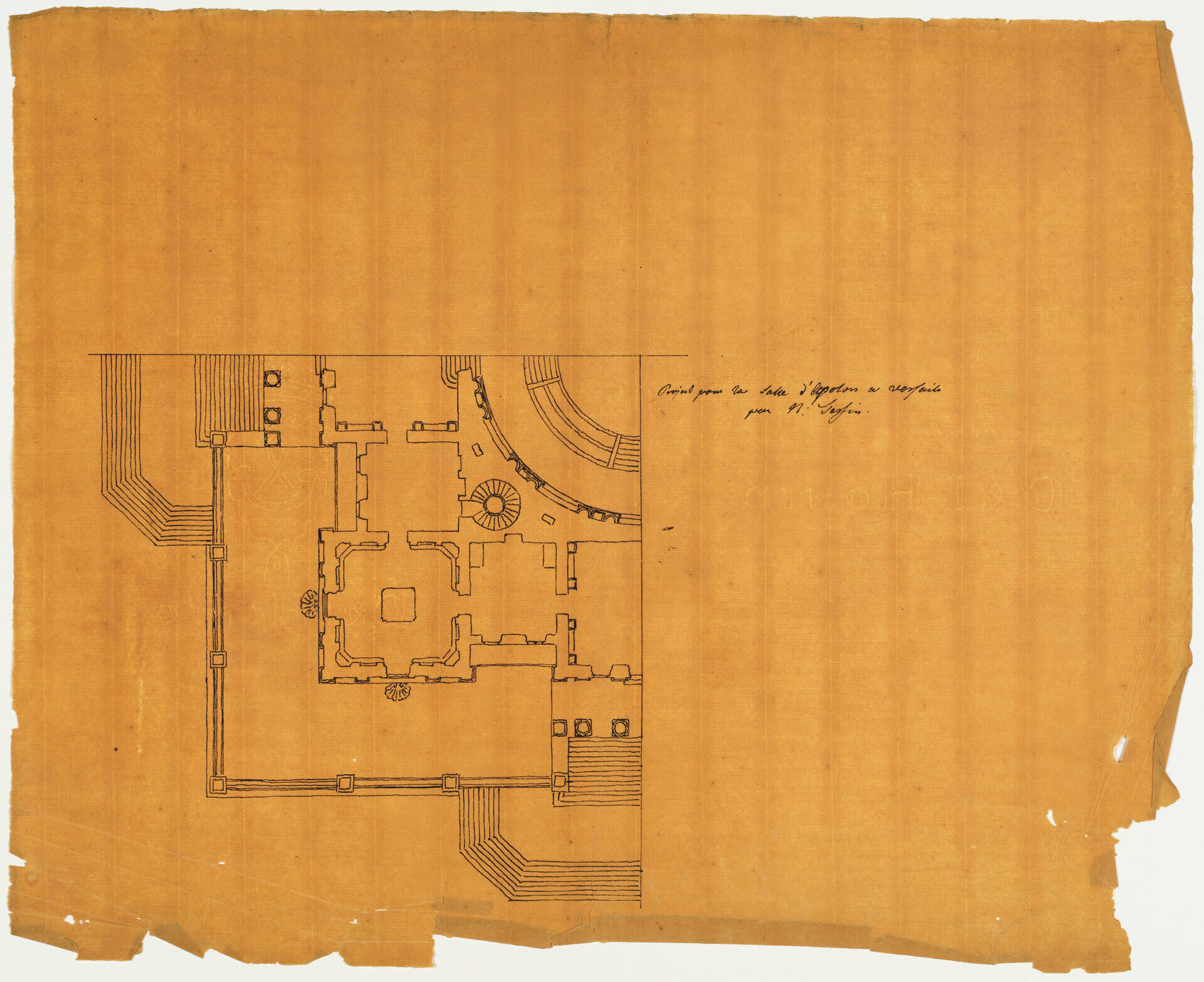

Carl Johan Cronstedt (1709–1777) after Gustaf Palmcrantz, Plan for a Temple of Apollo at Versailles, one quarter. Pen and black ink on tracing paper, 39.2 × 48.6 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH A CC 50.

Transparent paper as a design aid

The number of tracings in the Cronstedt collection (about 400, twice as many as in the Tessin–Hårleman collection) show that he not only used transparent paper in a more effective way than his master had done, but also to a greater extent.

The presence of tracings that featured not only designs by other architects but also projects conceived in Cronstedt’s own workshop suggests that, by the mid eighteenth century, transparent paper was being used by Swedish architects as a design tool.

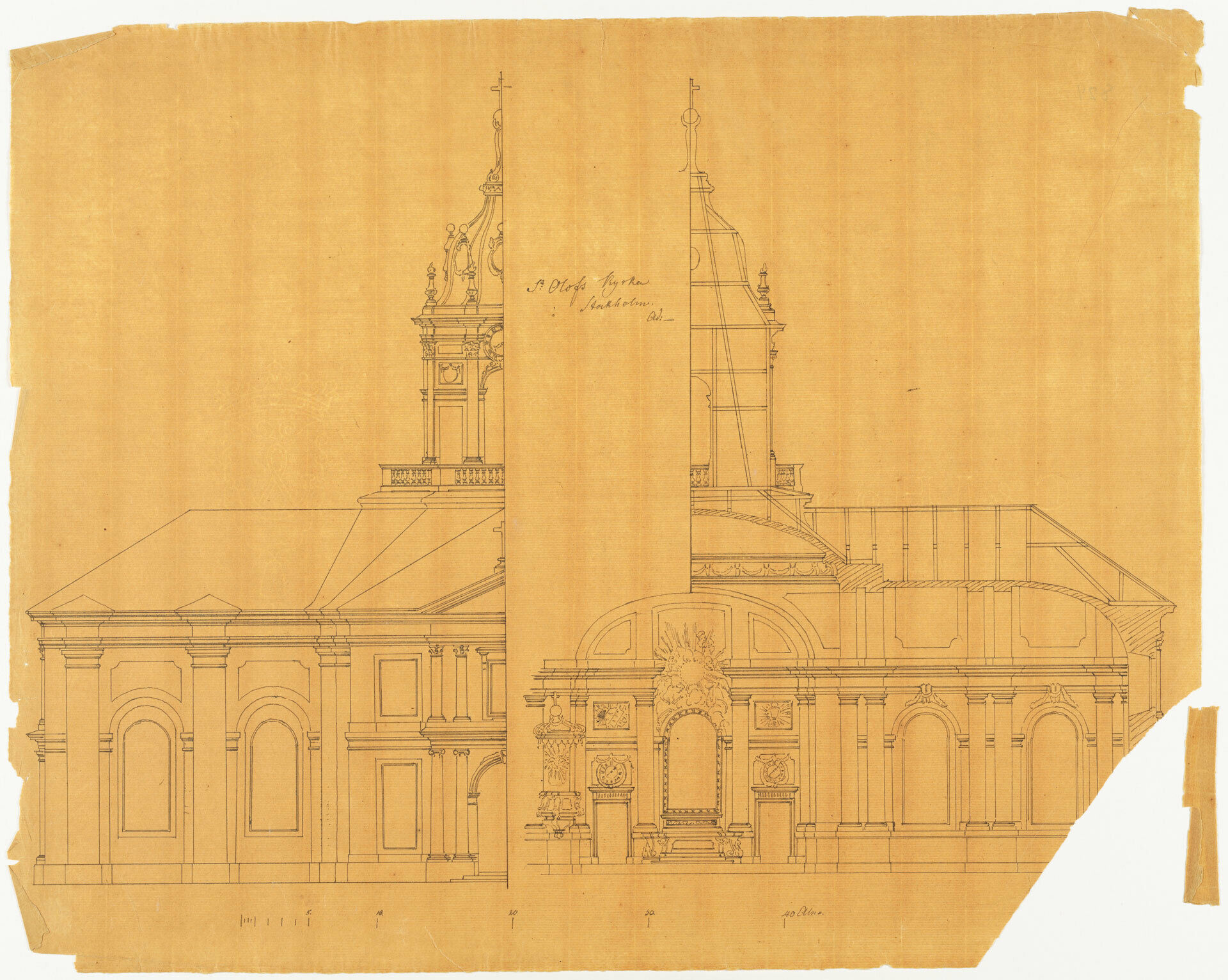

Carl Johan Cronstedt (1709–1777), Church of Adolf Frederick, Stockholm, half elevation, section. Pen and black ink on tracing paper, 38.8 × 48.6 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH A CC 234.

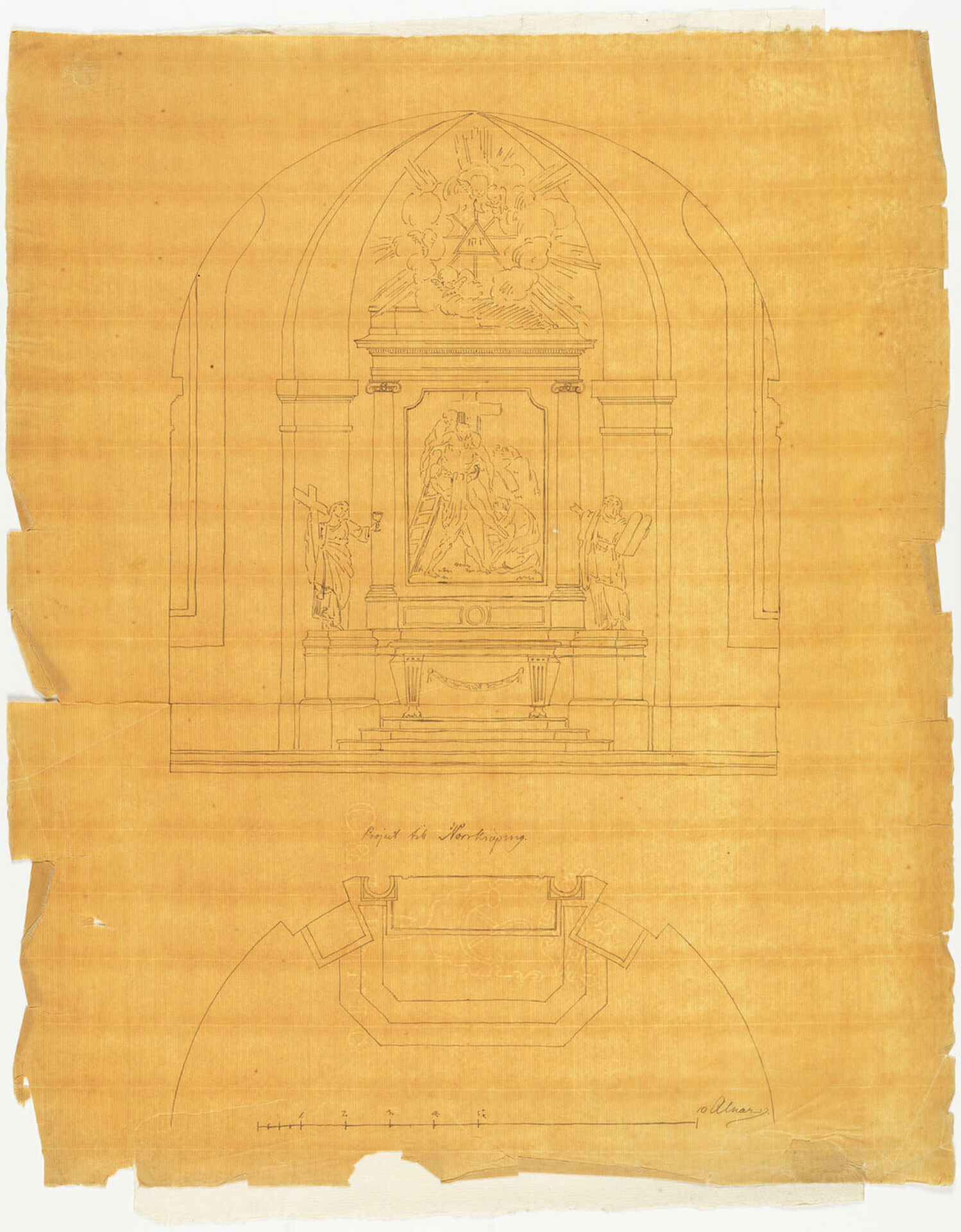

Carl Johan Cronstedt (1709–1777), Apsidal chapel and altar of St Olai Church, Norrköping, elevation and plan, c.1766. Pen and black ink on tracing paper laid onto a sheet of thick rag paper, 48.1 × 39.5 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH A CC 296.

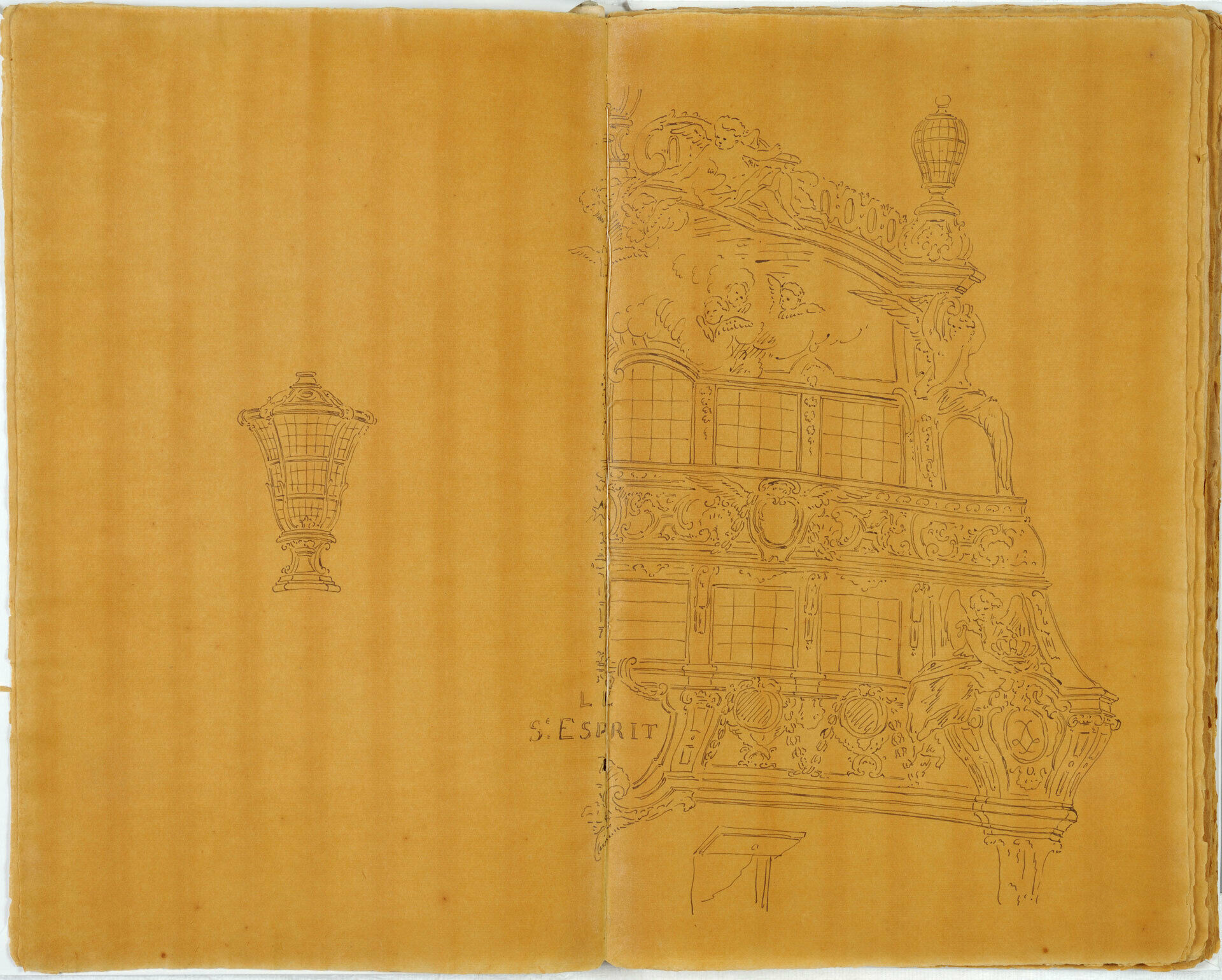

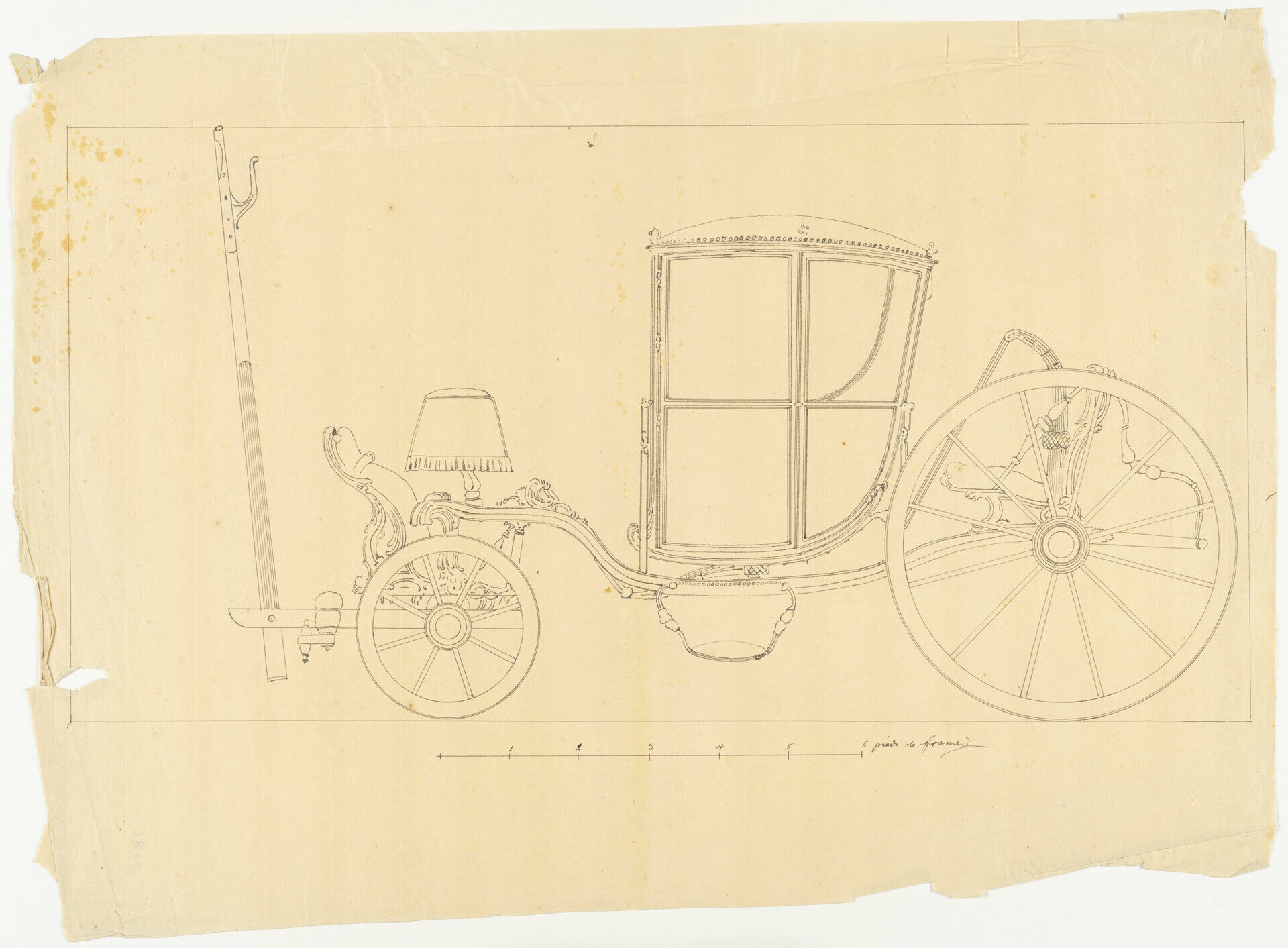

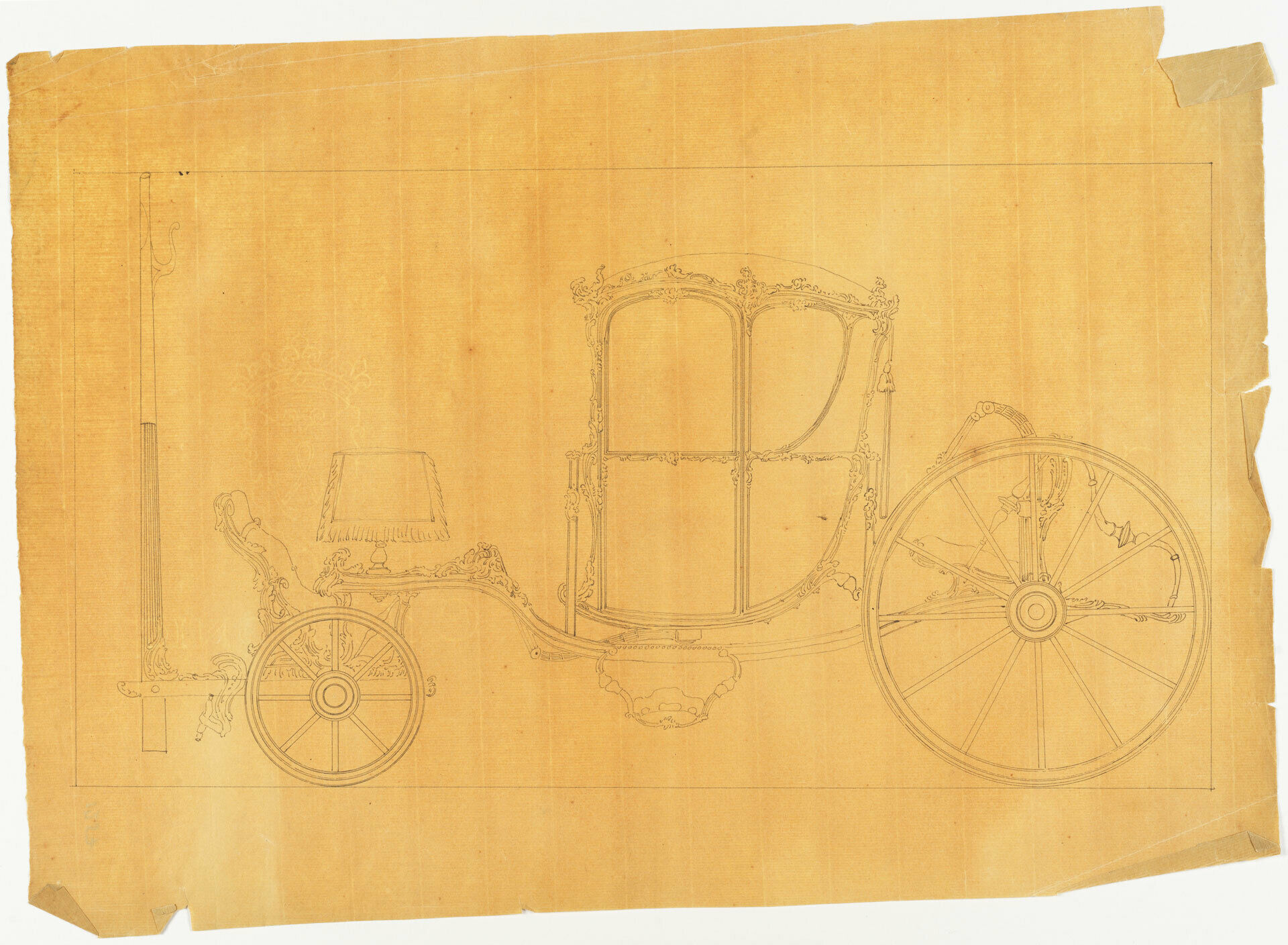

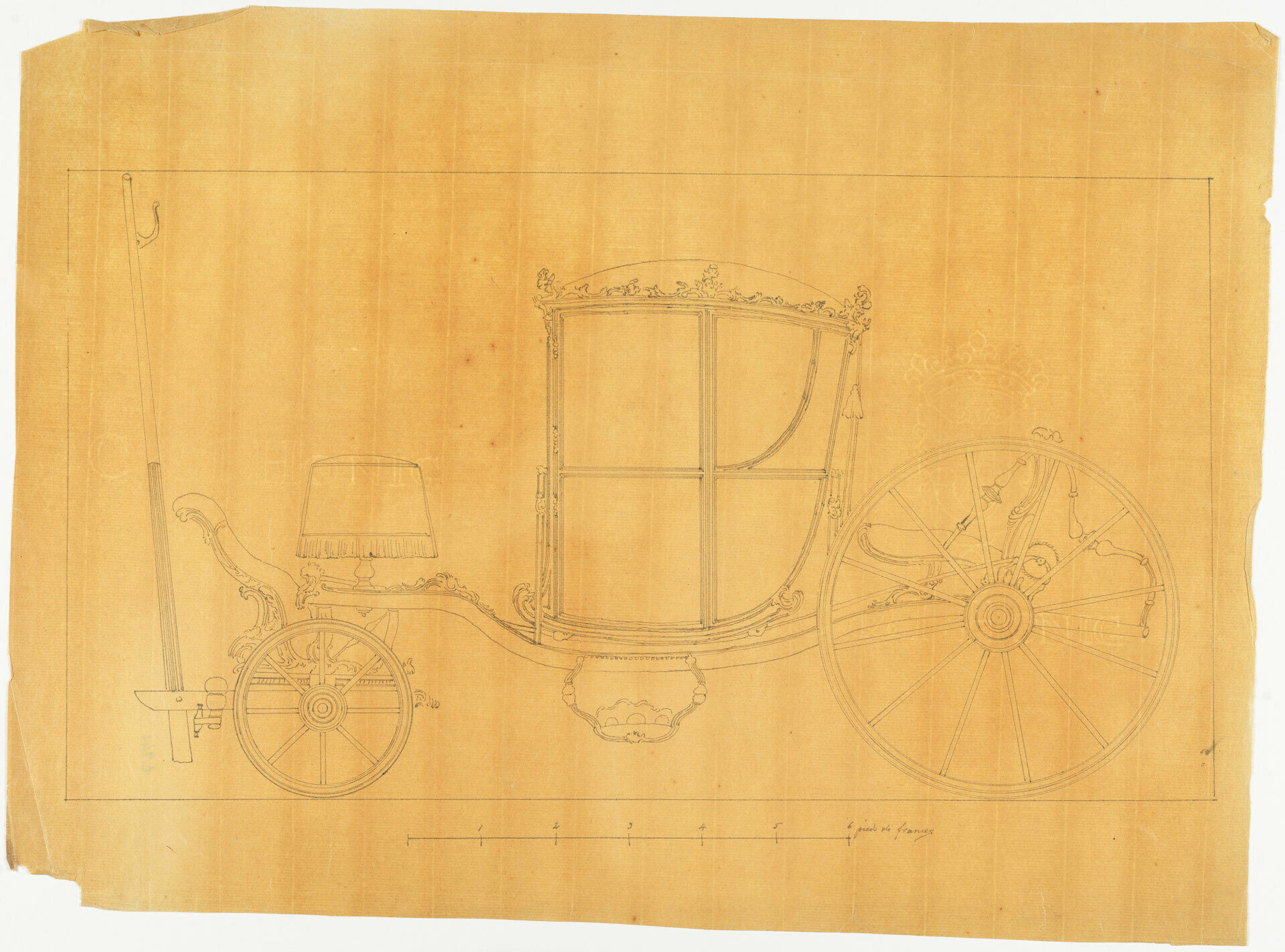

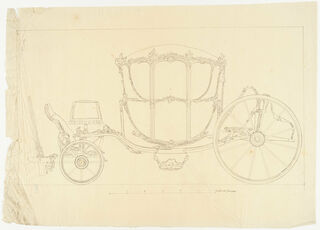

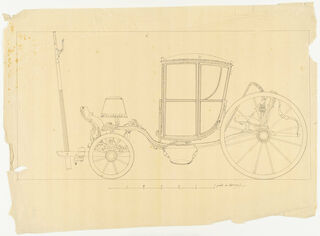

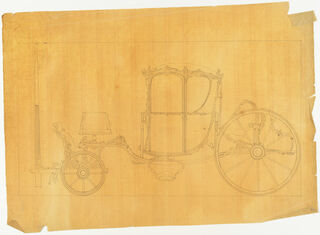

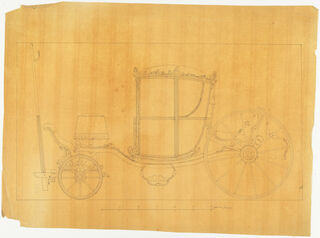

An example of this practice was a set of drawings for royal coaches. The drawings and the tracings of the same project are not exact copies of one another but pieces of a series, as they differ in one or more decorative elements. These sheets show how transparent paper helped Cronstedt to transfer preliminary designs onto a new sheet of paper in order to compare alternative solutions visually or to study the effect of the final design. When selecting the desired solution, the rapidity with which a tracing could be made of a drawing was doubtless an extraordinary aid for the architect. Cronstedt’s intuition of how tracings could be used as operative tools for architectural designs anticipated the much wider use Modernist architects made of industrially produced tracing paper as a ‘design environment’.

Carl Johan Cronstedt (1709–1777), Coach in profile. Pen and black ink on white laid paper, 34.6 × 48.3 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH A CC 216.

Carl Johan Cronstedt (1709–1777), Coach in profile. Pen and black ink on white laid paper, 34.5 × 48.4 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH A CC 214.

Carl Johan Cronstedt (1709–1777), Coach in profile. Pen and black ink on tracing paper, 34.3 × 48.4 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH A CC 211.

Carl Johan Cronstedt (1709–1777), Coach in profile. Pen and black ink on tracing paper, 34.8 × 47.3 cm. Nationalmuseum NMH A CC 212.

Video

The guest curator Anna Bortolozzi examines the Nationalmuseum's collection to uncover the architectural tracings and reveal the process of making and using transparent paper in the workshop.

Literature

- Anna Bortolozzi, ‘Transparent Paper as a Medium of Copying and Design in the Early Modern Architectural Workshop‘, RIHA Journal 2024, ID: 0319.

- Basile Baudez, ‘De l’usage du calque d’architecture à la fin du XVIIIe siècle, outil de conception ou mémoire de représentation’, in Claude Mignot (ed.), Le dessin d’architecture dans tous ses états: Le dessin d’architecture, document ou monument? (Paris 2015), 89–96.

- Basile Baudez, ‘Usage du calque dans le voyage de Naples, architectes et peintres au tournant des XVIIIe et XIXe siècles’, in Cristina Cuneo & Antonio Brucculeri (eds), À travers l’Italie: Édifices, villes, paysages dans les voyages des architectes français/Attraverso l’Italia: Edifici, città, paesaggi nei viaggi degli architetti francesi, 1750–1850 (Milan 2020), 166–173.

- Fabio Colonnese, ‘Between the Layers: Transparent Paper as a Modernist Architectural Design Environment’, in Cristiana Bartolomei, Alfonso Ippolito & Simone Helena Tanoue Vizioli (eds), Digital Modernism Heritage Lexicon (Cham 2021), 57–80.

- Helen Evans, ‘A Condition Survey of the Architectural Drawings Collections’, Art Bulletin of the Nationalmuseum, 16 (2009), 127–130.

- Claude Laroque, ‘History and analysis of transparent papers’, Paper Conservator, 28/1 (2004), 17–32. Claude Laroque, ‘Transparent papers: A technological outline and conservation review’, Reviews in Conservation, 1 (2000), 21–31.

- Magnus Olausson & Rebecka Millhagen (eds), Carl Hårleman: Människan och verket (Stockholm 2000).

- Linnéa Rollenhagen Tilly, Carl Johan Cronstedt: Arkitekt och organisatör (Stockholm 2017).

Credits

- Research, exhibition concept, and texts: Anna Bortolozzi, Nationalmuseum/Stockholm University

- Research and project coordination: Sarah Ferrari, Nationalmuseum

- Consultation: Karin Wretstrand, Nationalmuseum, and Helen Evans, Nationalmuseum

- Photography: Cecilia Heisser, Nationalmuseum

- Web editing: Åsa Melin Brisling, Nationalmuseum

This digital presentation is made possible with support from Getty through The Paper Project initiative.