Treasures from the Archive

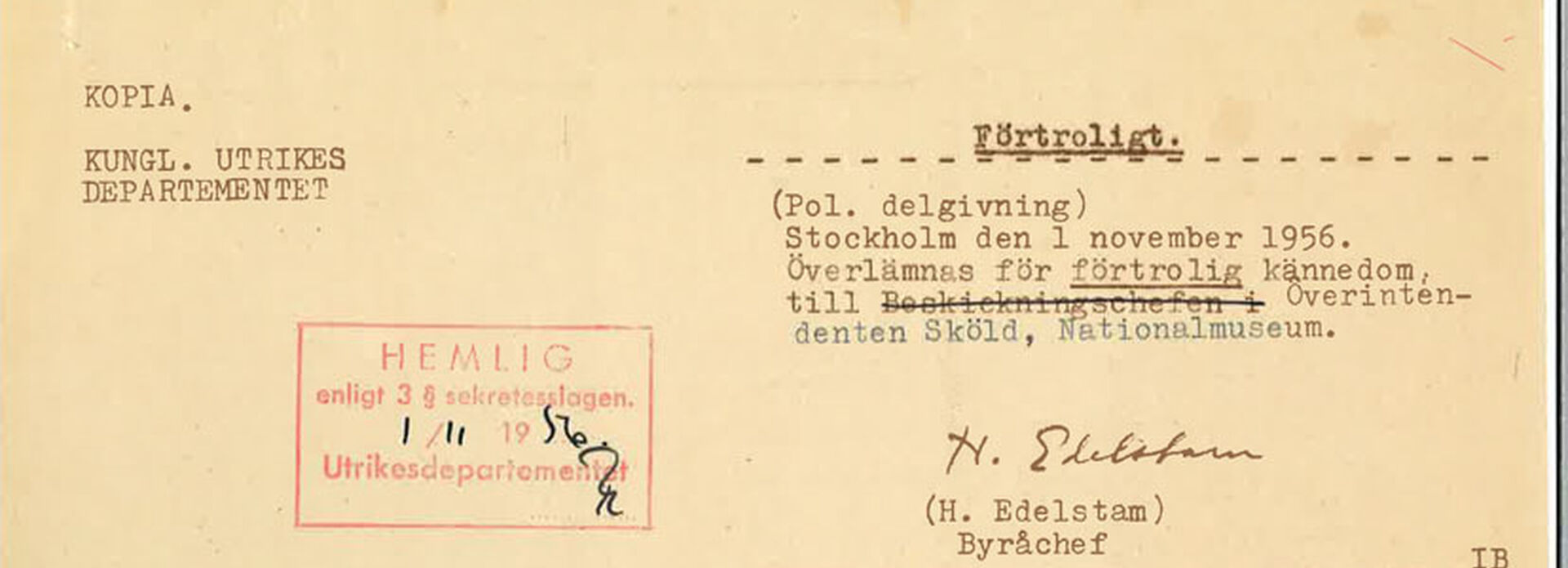

A Spanish scholar researching the exhibition history of Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937) recently visited the Nationalmuseum archives. Two of the items requested were unusual from the museum’s perspective: two memos issued by the political section at the Swedish foreign ministry. These 60-year-old classified documents that had been hidden away in the archives suddenly brought alive the issue of museums’ independence from political control.

The documents, which had long since been declassified, were sent to Nationalmuseum’s then director general, Otte Sköld, for information in autumn 1956. In the memos Leif Belfrage, the under-secretary of state for foreign affairs, reported that the Spanish ambassador had visited him on two occasions during the autumn to express concern over what he perceived as negative propaganda targeting the Spanish government.

The cause of the ambassador’s grievance was Picasso’s mural-sized painting Guernica, which was being exhibited at Exercishallen, the future home of Moderna Museet, on Skeppsholmen in Stockholm. “The greatest and most significant propaganda poster of our time against the futility and barbarity of war,” wrote Otte Sköld in the exhibition catalogue, which became No 1 in Moderna Museet’s catalogue series. The work had previously been exhibited in Sweden at Liljevalchs Konsthall in 1937, just one year after the massacre in the Basque city of Guernica, but on that occasion it had attracted little attention. This time it was a different story.

The ambassador complained that he himself had been invited by Nationalmuseum to attend a screening of a film with a communist slant about the Spanish civil war. What was more, the exhibition catalogue contained a selection of international press cuttings from the time of the civil war, and these too exhibited a critical attitude towards the Spanish regime.

The ambassador said that he had hesitated in sending the catalogue to Madrid, but that influential Spaniards who had seen the exhibition had now asked him to lodge a complaint. Belfrage replied initially that Nationalmuseum’s management had certainly not had any political motivation in producing the catalogue, but had simply wanted to portray the background to the artwork and the atmosphere in which it was created. This was stated in the introduction to the catalogue.

On his second visit, the ambassador continued to object, and Belfrage eventually made it clear that Nationalmuseum operated completely independently, and the government could not interfere in the museum’s activities. The second signatory to the memo from the foreign ministry was Harald Edelstam, then head of the political section, who later served as Sweden’s combative ambassador to Chile during the 1973 military coup.

With this in mind, it is interesting to read the information on the current Swedish government’s website about the proposed legislation governing museums, which includes a specific provision safeguarding museums’ independence from political decision-making.

Link to the government’s cultural heritage bill (2016/17:116) with provisions governing museums (in Swedish)

Proposition om kulturarvspolitik (1916/17:116)

Download PDF of both memos (in Swedish)

//Gertrud Nord, Archivist, Nationalmuseum Archives